What is a Budget?

Budgets provide the organizing framework for planning and the primary tools for controlling spending.

It is a universal rule in every well-run business that spending must not occur haphazardly. In principle, someone must plan, authorize, approve, and track every purchase or payment. The primary tool for managing these spending activities is the budget.

In its simplest form, a budget is a spending plan or forecast written as a list. The list shows spending items and incoming revenue items for a specific time. A completed budget is the outcome of a budgeting process whose purpose is to provide a budget figure for each budget item.

Define Budget and Budget Purpose

In business, a budget is a plan for an organization's outgoing expenses and incoming revenues for a specific time span.

Most businesses create budgets for these purposes:

- To plan, track, and control spending.

The purpose is to ensure that spending follows a plan, supports business objectives, stays within preset limits, and does not exceed available funds. - To support funding requests.

The purpose is to justify funding proposals by showing how the proposal author will use them.

In large entities, the Budget Office Director and staff work with individual managers and others seeking funding approval. As a result, budget proposals conform to local policies and the entire proposal package aligns with group objectives. [Photo: Business office manager and staff, The New York World, New York, 1909]

Budgeting Explained in Context

The sections below further define and explain budget and budgeting. Budget examples appear in context with related terms from the fields of budgeting, accounting, and business analysis, focusing on four themes:

- First, defining budgeting terms such as variance, OPEX, and CAPEX.

- Second, budgetary planning and the budget cycle for capital and operating budgets.

- Third, cash budget examples and usage

- Fourth, comparing static, flexible, incremental, and zero-base budgeting.

Contents

The Meaning of Budget and Budgeting

What Does a budget Variance Reveal?

The simplest budget in business is essentially a list of spending items and incoming revenues for a specific period (such as fiscal year), or a series of periods (such as a month). The list shows spending items and incoming revenue that are either planned or forecast across the time span. Each spending item or revenue item is assigned a monetary figure during the organization's budgeting process is to provide a budget figure for each budget item.

As time passes, actual spending and revenues enter the list to compare with original budget figures. Where budget and actual figures differ, the difference is called a variance.

Defining Budget Variance

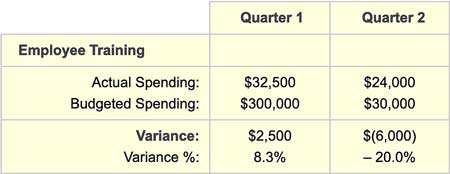

A firm's operating budget, for instance, may forecast spending for "Employee Training." The annual spending figure is set first, for high-level planning. Later, the firm will break down the yearly figure into monthly or quarterly data.

Suppose that two quarters into the budget cycle, the item "Employee Training" looks something like Exhibit 1:

Most budget analysts calculate variance by subtracting the budget figure from the actual spending figure. They publish both numbers because both are helpful, later, for variance analysis.

Conventions for Variances, + and –

Note, by the way, this example uses a convention common in finance, budgeting, and accounting. Here, the figures in parentheses are negative values.

Note also that analysts use two different and opposite sign conventions for showing variances.

- Firstly, the example above uses the first convention. The example shows variance as actual spending less than the budget figure.

Convention 1: Variance =Actual spending – Budgeted spending

As a result, a variance greater than zero spending is over budget while a negative figure means spending is under budget. - Secondly, note that some people instead show variance as the budget value less the actual figure.

Convention 2: Variance = Budgeted spending – Actual spending

In that case, overspending results in a negative figure.

Businesspeople use both conventions, and neither is incorrect. What matters is that everyone in the firm uses the same practice, consistently.

Responding to Budget Variance

In the real business world, small differences between actual and budget figures are normal and expected. Given a significant variance, however, leaders want to know, exactly why actual results are so far off target. The answer to the "Why" question may be transparent, or it may call for serious variance analysis. In any case, they can respond with one or both of these actions:

- Adjust the forecast to reflect the new reality.

This response is known as flexible budgeting. - Control actual spending in the future, to bring the annual variance closer to zero.

What is a Budget Hierarchy

Which Budgets Have Hierarchical Structure?

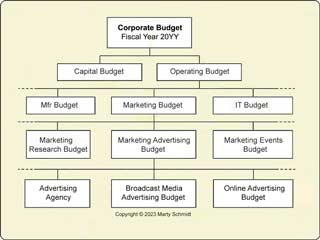

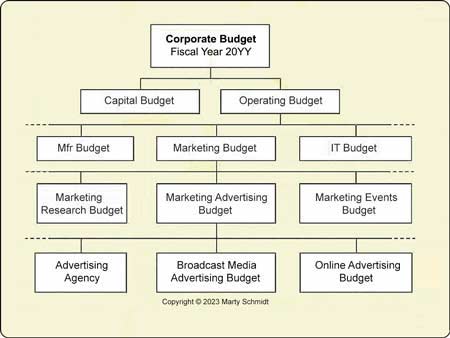

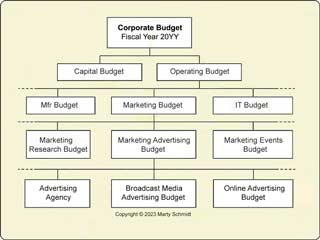

Budget planning begins with high-level budgets, primarily the entity-wide capital and operating budgets.

- Some firms plan the capital budget on a company-wide basis, choosing not to specify individual department budgets further. Budget items for the high-level capital budget may nevertheless appear in categories. These may represent significant components of the firm's asset structure, such as "Inventory purchase."

- On the other hand, large firms almost always plan spending and revenues for the operating budget in the framework of a budget hierarchy.

- Individual line items in the top-level operating budget may carry the names of departments or groups, such as "Marketing." Or, items may be the names of fundamental roles, such as "General management and administration."

- In the budgeting process, senior managers first set spending levels for higher-level categories such as the "Marketing Budget." Then, Marketing managers further apportion this into lower-level budgets for areas such as market research, advertising, and events.

- Ultimately, every cost object for the firm appears in a budget, either as an item in its own right or within a budget category.

The two top-level budgets together essentially cover spending for the entire firm. Other, budgets may exist for areas such as investments, contingencies, or sinking funds, but these usually are quite small relative to the capital and operating budgets.

Exhibit 2 shows a few of the levels in one firm's budget hierarchy:

Capital Budget vs. Operating Budget

What Are the Differences?

Two major kinds of plans usually stand at the top of the budget hierarchy. One is the budget for capital expenses or CAPEX. The second is the budget for operating expenses or OPEX. CAPEX and OPEX handle entirely different spending items, and thus do not overlap. Moreover, firms create capital and operating budgets through different kinds of budgeting processes, involving different managers. Those preparing funding requests should keep in mind these points:

- First, capital and operating budgets usually apply different criteria for prioritizing requests and deciding spending.

- Second, many proposals include both CAPEX and OPEX spending. As a result, those asking for funding in such cases must state what they need from the capital budget and what they need from the operating budget.

- Third, as a result, the wise manager, therefore, writes the funding request and its business case with an eye on both sets of decision criteria.

In brief, those who submit funding requests are asking their employers to spend. Proposal writers serve their interests, therefore, by learning thoroughly how the entity plans and decides how to use funds.

Capital Spending CAPEX vs. Operating Expenses OPEX

Whether an expense item is CAPEX or OPEX depends on the nature of the purchase and how owners use it. The country's tax laws may also help determine what a capital item is and what it is not.

Most entities aim to achieve consistency in accounting and conformance with tax laws. For this reason, many define specific criteria that qualify spending items as "capital." One firm might, for instance, require a useful life of at least one year and a purchase price over $1,000. Some may also need capital acquisitions to support the firm's regular line of business. In any case, only expenditures meeting the capital criteria qualify as CAPEX. Those that do not are, as a result, OPEX spending.Pat4iciaA

Defining Capital Budget CAPEX

What Does the CAPEX Budget Cover?

Capital budgets forecast spending for capital expenditures (CAPEX), usually means acquiring capital assets. Additions that meet the entity's criteria for "capital" items are almost always long lasting, expensive items, which contribute to the value of Balance sheet assets.

In large entities, capital budget planning is usually a Budget Office responsibility of a Budget Office. Or, in some settings, the Budget Office and a Capital Review Committee share that responsibility. These groups establish criteria for prioritizing proposals and for setting a capital spending limit, the capital budget ceiling. The term capital funds applies to funds designated for the capital budget.

Typical Capital Budget Items

Capital expenses (CAPEX) cover purchases that meet company and government criteria as capital assets. Capital purchases typically include items such as these:

Evaluating Capital Proposals

With a capital spending ceiling in place, the Capital Review Committee is ready to accept capital proposals. Committees usually invite submissions from the entire entity. Increasingly, reviewers require them to include business case support. The business case is necessary because capital reviewers approve funding only if confident on three points:

- First, the proposal has financial justification.

- Second, the proposal comes with acceptable risk levels.

- Third, the proposal aligns with strategic objectives.

The Competitive Capital Review Process

It is also usual for the sum of incoming funding requests to exceed the capital spending ceiling. As a result, proposals must compete for funding. Reviewers will then use business case results to help prioritize funding requests. Proposals typically receive funding authorization in order of priority. Approval starts with the highest priority proposal and continues until the total reaches the capital spending ceiling.

Capital review committees usually establish and publish their criteria for prioritizing proposals and making funding decisions. Not surprisingly, they typically choose standards that address the three areas mentioned above, financial justification, risk, and strategic alignment. Proposal authors, therefore, know while writing their proposals, which points will decide the proposal's fate.

Three Kinds of Criteria for Evaluating Capital Proposals

Essential criteria for evaluating proposals may, therefore, include the following:

First Criterion, Financial Criteria

These criteria address questions such as these:

- Will the investment return a profit?

- How does profitability for this investment compare to other options?

- How long will it take for the investment to pay for itself?

Financial metrics that help address these questions include:

- Net present value (NPV)

- The internal rate of return (IRR)

- Return on investment

- Payback period

Second Criterion, Risk Criteria

When evaluating capital investment proposals, companies also consider risks. Risk refers first to the level of uncertainty in forecast returns. Secondly, the term also refers to risk factors that could lower returns, raise costs, or disrupt the investment schedule.

Third Criterion, Strategic Alignment

Companies also evaluate capital funding requests for strategic consistency (strategic alignment). They ask, in other words, how outcomes align with strategic objectives.

Capital Reviews Have Entity-Wide Scope

Competitive capital reviews, incidentally, usually have an entity-wide scope. CAPEX proposals frequently compete for high-priority status against others from across the entire entity. By contrast, requests for OPEX funding typically compete only against others in the same budgetary unit (e.g., Marketing Advertising Budget).

In brief, those who propose capital spending or request capital funding should be sure they understand fully:

- Local criteria for prioritizing capital spending proposals.

- Calendar dates of the current and next capital planning and spending cycles.

- The current capital spending ceiling.

Financial Reporting and Capital Spending

- Capital Items on the Income statement capital do not turn entirely into expense in one year in one year.

- Instead, capital acquisitions impact the Income statement and Balance sheet by creating depreciation expense.

- Depreciation itself is a noncash expense. Nevertheless, accountants charge depreciation against sales revenues to help calculate "bottom line" profits.

- This noncash expense does have one impact on real cash flow. For entities that pay income taxes, depreciation lowers reported income. This impact, in turn, reduces the firm's tax liability. Depreciation expense, in other words, bring tax savings.

- Depreciation also impacts the value of the entity's asset base on the Balance sheet. Each year of an asset's depreciation life, its book value decreases by the depreciation expense.

- Tax authorities determine which expenditures for a business start-up, for instance, qualify as capital costs.

- Entities usually report costs of services as OPEX, not CAPEX. In the United States and a few other countries, however, they sometimes "bundle" services costs into the full capital costs of acquiring assets. For example, a substantial capital project may result in a capital asset such as an IT system. Here, Services such as systems integration consulting, serve as legitimate capital costs.

Defining Operating Budget OPEX

What Does the OPEX Budget Cover?

Not surprisingly, the operating budget covers operating expenses (OPEX) for normal operations. The operating budget, therefore, covers spending on items that are not part of Balance sheet assets. These typically include predictable recurring charges for such things as salaries and wages or utility costs. OPEX also include, of course, items the firm acquires irregularly, such as outside consultant services or employee training.

Entities usually develop the operating budget using a process different from the CAPEX budgeting process. In some organizations, all managers above a certain level participate in the process. Budget figures for operating expenses, once set, usually do not change during the period. (Exceptions include emergency reductions following unexpectedly poor sales results or other disasters). In other words, OPEX budgets are usually static budgets, not flexible budgets.

Typical Operating Expense Spending Items

Standard OPEX budget items include, for example:

Financial Reporting and Spending on Operating Expenses

OPEX spending impacts the Income statement directly. It does not affect the Balance sheet directly.

- For the Income statement, operating expense items are fully expensed in the year they occur. OPEX spending "goes straight to the bottom line," impacting the earnings report only in the same reporting period.

- Spending on operating expenses does not bring depreciation expense.

Operating expenses reflects a budgeting term vs. operating expenses as an Income statement category

Note that there is also a significant Income statement category called "Operating Expenses." This name, therefore, has one meaning for budgeting and a slightly different interpretation for Income statement reporting.

- Income statement Operating Expense items appear below the Gross Profit line and therefore have no impact on reported gross profits or gross margin.

- When used in the budgetary sense, however, the term operating expense can include expense items above the gross profit line. Direct labor wages in product manufacturing, for instance, appear above gross profit, as part of Cost of Goods Sold.

What is A Cash Budget?

Cash Budgeting Explained with an Example

A cash budget is a tool for planning and controlling near-term cash inflows and outflows. In business, cash budgets are like the check register that individuals use to manage a personal checking account. The cash budget and the check register both record incoming and outgoing transactions, as they occur. As a result, the owner can see immediately the level of cash on hand.

Cash Budgeting vs. Accrual Accounting

Cash budgets typically have a series of months in view, although they can also show cash revenues and spending for weeks, quarters, or years. In all cases, however, the cash budget shows actual cash flows, only in the period they occur. This usage contrasts with the system of accrual accounting which most companies use for financial reporting. Accrual systems report receivables and liabilities for the period they occur, but cash flows that follow may occur in another period.

Cash Budget Example

A small firm's monthly cash budget may look like Exhibit 3:

The example cash flow budget shows the budget as it stands in mid-February. Figures for January are now history and will not change. "Actual" data for February are current as of mid-month, but these may change by the end of the month.

Cash Budget Variances

This example cash budget includes three kinds of figures:

- Forecast inflows and outflows,

- Actual inflows and outflows.

- The difference between actual and forecast figures for each line item—a Variance.

In Exhibit 3, the variance is the actual figure less the forecast figure. With this convention, a "variance" higher than 0 means that actual cash flow exceeds forecast. A variance of less than 0 shows that actual spending was under the budget.

Notice especially in the example the actual cash on hand balance at the end of January. Here:

The final actual cash balance for January carries over to February as actual starting cash for that month.

When large variances appear between forecast and actual inflows or outflows, the cash budget helps identify the source of the deviations. In the example above, the overall negative cash flow variance for January was not due to overspending in that month. Instead, the variation is there because product and service sales revenues fell below forecast. For future months, the manager has two kinds of responses available:

- Take action to increase incoming revenue.

- Lower the forecast revenues and spending figures.

The Budgeting Process

How Process Works in the Budget Planning Cycle

Business entities usually develop and use budgets on a periodic basis at fixed intervals. The norm in private industry is to produce a budget for each fiscal year. Some government groups also prepare annual plans, but two-year (biennial) budgets are also typical in government.

Once the budget cycle is underway, the usual practice is to leave budget forecasts intact (static). Management in some instances adjusts these projections in "real time," but such changes are exceptions to the standard rule. Usually, entities change predictions only in response to exceptional events or circumstances.

Defining Budget Cycle and Budget Process

In the period between the issuance of one budget and the next, planning-related decisions and activities make up the budget cycle or budget process. In large entities, the process typically extends across months, if not the entire period between budgets.

For those working on budgeting, the process calls for many specific steps and requirements. Not surprisingly, the nature and timing of these vary widely among entities. Most large organizations publish a description of their process, calendar, and approval requirements on their internal network. This information is sometimes open to the public, and occasionally accessible only to employees with authorized access to it. In any case, those setting out to prepare a funding request for the first time usually begin by accessing this source.

Steps in the Budget Process

Although specific steps and timing vary from entity to entity, the budgeting process everywhere almost always includes steps for:

- Assessing variances between actual and budgeted figures in the previous period's plan.

- Identifying and then prioritizing business needs and objectives for the forthcoming period.

- Forecasting and evaluating the following:

- Incoming revenues.

- Current trends or changes that have implications for spending or revenue inflows. Particular attention may focus on new mandates to reduce spending or changes in staffing levels or changes in business volume.

- Risks or emergencies that could impact incoming funds or spending needs. The budget, in other words, may need to anticipate events such as labor action, competitor action, or natural disasters.

- Ensuring that …

- Individual funding proposals in the complete plan are consistent in format. As a result, competing requests are subject to fair comparison.

- Funding proposals align with strategic objectives.

- Procedures and methods are in place for implementing monitoring the plan.

- Packaging and communicating funding requests to those responsible for reviewing and approving budget proposals.

In large entities, the responsibility for driving and managing the budgeting process belongs to a Budget Office. This office works directly with managers, department heads, and others, to help shape their funding proposals. It also works at the same time with senior managers, legislative bodies, and senior officials who approve spending. The result is that all budget proposals conform to local policies and rules and that the entire proposal package is reasonable and aligned with entity objectives.

Explaining Zero-Based Budgeting

Zero Base Budgeting VS Incremental Budgeting?

Zero-based budgeting is an approach requiring justification for every expenditure. In other words, each spending item starts with a budget value of 0. Those requesting funds must justify all changes above 0. This requirement contrasts with the more usual practice, incremental budgeting. Under this method, each spending item starts at last term's level. The next term's budget is an increment to that level (positive or negative change).

Advocates of zero-based planning favor the approach because it focuses on demonstrating needs and resources. Zero-based budgeting is blind to historical spending levels. As a result, arguably, resource allocation is more efficient. The zero-based approach can be very successful, for instance, in finding and trimming inflated budgets. It can be helpful for exposing budgets that include obsolete or wasteful operations.

Zero Base Budgeting vs. End of Period Spending.

Zero-based budgeting also helps avoid a practice for which the incremental approach is notorious. This practice usually occurs just as the budget period nears an end. Some managers seem to spend solely for the sake of using up their budgets. In such cases, they empty the budget, whether that spending is necessary or not. This practice no doubt reflects a belief they must spend all of this period's plan, or else receive less next period. In some entities, experience confirms this belief. In brief, this kind of period-end spending is a serious risk under incremental budgeting. Under zero-based budgeting, however, this tactic would be pointless.

In a large entity, however, the zero-based approach may call for very substantial research and analysis to justify every funding request—an investment in time and organizational resources that is not, in its own right, justified. Under the Incremental approach, formal justification (for example, a business case analysis) is usually required only for capital spending proposals or for significant spending increases in operating expense categories.

What is Budget Variance Analysis?

How Does Variance Analysis Work With Flexible Budgeting?

Variance (a difference between actual and forecast figures) is a signal that revenues or spending did not go according to plan. If the variation represents overspending, moreover, it is a warning there may be problems paying future expenses. Variance analysis attempts to find the reasons that actual figures were over or under forecast so that either …

- Management can take corrective action to reduce variances in the future, (an exercise in static budgeting).

- Budget authorities can adjust budgets for future spending as necessary (the practice of flexible budgeting).

Sign Conventions in Variance Analysis

Confusion sometimes arises in variance analysis because two different conventions for calculations commonly used.

- Convention 1

Incoming revenue variance = Actual – Forecast

Expense spending variance = Actual – Forecast

This convention appears in this encyclopedia and is the preferred approach in many entities. Under this approach, a variance greater than zero always means actual spending was higher than the budget amount. - Convention 2

Some entities (such as the Project Management Institute), however, recommend using the above rule for revenue, but reversing the order for expense items:

Incoming revenue variance = Actual – Forecast

Expense spending variance = Forecast – Actual

Under Convention 2, variances above zero are always "good things" (more revenue or less spending than expected), and negative variances are always "bad things."

Indeed, anyone involved in planning and analyzing spending needs to know which convention applies in their organization.

Variance Analysis Step 1:

The Variance Report

In many companies, variance analysis becomes especially important in planning for two areas:

- Direct and indirect manufacturing costs.

- Sales revenues and sales costs.

Revenues and expenses in these areas are often difficult to predict accurately. Variance analysis for these areas is, in fact, a complex and challenging topic for cost accountants. The purpose of the example below is simply to illustrate the nature of the task.

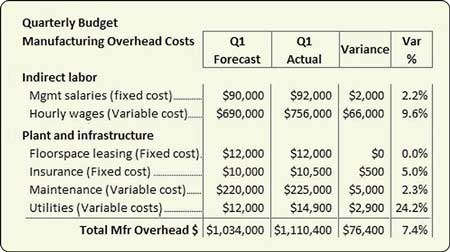

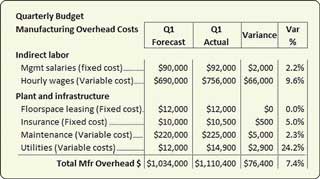

Variance analysis typically begins with variance reports at the end of each month, quarter, or year, showing the difference between actual spending and forecasted spending. As an example, consider a small manufacturing firm's quarterly variance report for one plan item, "Manufacturing overhead." Exhibit 4 shows how the variance report might appear.

Note for instance that the variance report shows that Manufacturing overhead is $76,400 over plan for the quarter. The variance is 7.4% of the budgeted figure. The Manufacturing overhead variance is a substantial percentage of a significant budget item. Leaders will undoubtedly want to know the reason or reasons for the variation, and then what can be done to prevent recurrence in the next quarters.

Variance Analysis Step 2:

Cost Item Components and Their Variances.

The next step in variance analysis is to identify the components of the cost item (manufacturing overhead), and sources of variance within them.

The table above lists 6 line item components. Note that some of these are fixed costs, and others are variable costs. Fixed costs should not (in principle) depend on manufacturing volume and should be more predictable than variable costs. Nevertheles, management salaries (a "fixed" cost ) were $2,000 over forecast. The analyst will want to find the reason for the unexpected variance for management salaries.

Variance Analysis Step 3:

Variance Causes for Fixed Costs

A closer review of quarterly expenditures reveals the source of these fixed cost variances.

- It turns out that during the quarter, the four managers involved took a total of two weeks of sick leave with pay. As a result, other managers had to cover for them.

- Insurance costs (another fixed cost item) were 5% over forecast. Why? Here, there was an unexpected increase in insurance premiums during the quarter.

Usually, variances in fixed costs are due to:

- Surprising problems or emergencies

- Unexpected cost changes

- Underestimated need for utilization of fixed cost resources

Variance Analysis Step 4:

Variance Causes for Variable Costs

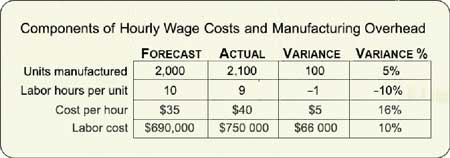

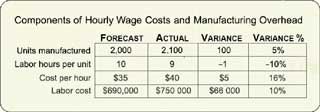

In the table above, two variable cost components of Manufacturing overhead costs stand out with large striking variances. The large-variance elements are Hourly wage costs (9.6% over plan) and utility costs (24.2% over budget). Of these, the hourly wage variance draws attention first because it represents a substantial part of the overall Manufacturing overhead variance.

Hourly wages are a variable cost item because they depend on manufacturing volume (units manufactured). Note, however, that two other variable factors also contribute total hourly wage costs. That is, labor hours per unit, and labor expense (here, dollars per hour) are themselves both variable costs.

Hourly wage costs are in fact the product of 3 variable factors:

Hourly wage cost

= (Units manufactured) * (Labor hours / unit ) * (Labor cost / hr)

Exhibit 5 shows how actual figures for these factors compare with the forecast:

To account for the actual labor cost, first, add 100% to each variance figure.

- Units variance is therefore 105% of forecast.

- Hours per unit variance is therefore 90% of forecast.

- Labor cost per hour variance is therefore 116% of forecast.

These percentages, multiplied together, account for the actual labor cost:

Actual hourly labor cost

= Forecast labor cost * 105% * 90% * 116%

= $690,000 * 105% * 90% * 116%

= $756,000

Variance Analysis Step 5:

Drawing Conclusions

Leaders may draw several conclusions from this analysis: :

- The positive variance in units is not a bad result. On the contrary, the higher unit count is probably due to greater sales revenues and profits.

- Unit volume forecasts are now higher for the next quarters. Leaders may now consider additional hiring, to complete work without extensive labor overtime.

- The overspending in average hourly wage rates should also move management to find ways to provide more labor hours at the standard rate instead of the much higher overhead rate. This variance provides additional evidence that management should consider additional hiring.

- The efficiency gain in hours per unit is also a good result. Management will ask if this can be sustained or even improved further. If so, the change may impact future spending forecasts.

Leaders can use the "Actual hourly labor cost" formula above to try out different proposal figures and variances, to see the impact on actual cost.

Also, the substantial variance for utility costs (24.2% over plan) bears looking into in the same way. The percentage is significant, even though the actual spending figures are small relative to the wage cost variance. The same analysis here, however, is more complicated. Utility costs represent several items, such as phone, water, and electricity. Each of these, in turn, involves the product of variances in price, efficiency, and usage.

Variance analysis Step 6:

Prescribing Solutions

A budget variance presents leaders with two alternatives:

- Adjust the budget in future periods to conform to revenue or spending realities.

- Or, take action to impact future spending and revenues, to bring forecast and actual figures closer together.

The former option (adjusting the plan) is called flexible budgeting. The latter option is an instance of static budgeting.

Most large entities permit at least a limited degree of flexibility in planning. Most managers responsible for lower-level budgets (e.g., for a department budget or an operational area such as "Advertising") can adjust their own plans "in real time" by moving planned levels from one category to another. Note, however, that movements from "capital spending" authorizations to "operating expense" is not always easy.

Most organizations recognize that managers occasionally must increase their overall spending total above the budgeted total. They sometimes call the process for requesting more funds in such cases "emergency funding" or "request for non-budgeted funds." Such requests go to the next higher management level. The higher level may designate funds specifically set aside for such contingencies. Or, if the requester can demonstrate need, these funds may have to come from current assets, such as cash on hand or the sale of stock the firm owns for investment purposes.