What are Selective Income Metrics such as EBIT?

Net income is not always the most helpful metric for evaluating the impact of management actions or strategy changes on earnings. Often, selective income metrics reveal impacts more precisely.

Business owners and analysts sometimes prefer to measure business performance in terms of Earnings Before Interest and Taxes EBIT and other "selective" metrics, instead of the familiar bottom-line Net Income metric.

Define Selective Income Metrics

The term Selective Income Metrics refers to a family of income statement metrics that measure an organization's earnings performance for a reporting period.

"Selective" means these metrics represent just a few selected items on the Income statement. They do not reflect all revenues and expenses. Their names begin with "Earnings before...," and end with a list of income statement items that do not enter the calculation.

These metrics are also known as "Earnings Before" metrics, or Focused Income metrics.

Earnings Before Interest and Taxes EBIT is the most familiar of the selective earnings metrics that analysts and financial specialists use to evaluate earnings performance. As the name suggests, EBIT measures earnings as Income Statement revenues less all expenses—except for interest and tax expenses.

The Purpose of Selective Income Metrics?

Selective Income metrics address questions like these:

- Is the company earning acceptable profits in its core line of business?

- Did the firm reach its objectives for earnings growth?

- How do company earnings compare to competitors?

Analysts address such questions by comparing earnings from the firm's latest Income statement to:

- Earlier Income statements.

- Competitors earnings.

- Industry averages and best-in-class standards.

Why Use Selective Income Metrics?

The first metric that comes to mind at the mention of earnings is Net Income, the all-inclusive income statement "bottom line." Net Income, however, can provide misleading answers for specific earnings questions. Net Income can be misleading when:

- The primary interest is income from the core line of business.

- There are significant expenses for items such as depreciation, interest, or taxes.

As a result, corporate officers and shareholders sometimes turn instead to selective income metrics such as EBIT, for a clearer view of the core line of business earnings.

The article further explains the purpose and use of "selective" earnings metrics. Sections below describe and calculate six favorite earnings metrics:

- Net Income

- Operating Income

- EBT

- EBIT

- EBITDA

- EBEITDA

Contents

- What are earnings before interest and taxes EBIT? And, what are "selective income metrics?"

- What is the purpose of "selective income metrics?" Where are they used?

- Explain the most-used "Earnings-before" metrics? How do they compare to Net Profit?

- Defining and calculating "Operating income" ("Operating profit," "Earnings from operations").

- Calculating and explaining "Earnings before taxes" (EBT, "Pre-tax earnings," "Profit before tax," PBT).

- Defining and explaining "Earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT)."

- Explaining and calculating "Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation & amortization" ("EBITDA," "Operational cash flow").

- Defining and calculating "Earnings before extraordinary items, interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization" (EBEITDA).

- Example Income statement for earnings metrics.

Related Topics

- Profitability as a measure of earnings performance: See Profitability.

- Three margins: Gross, Operating, and Net profit: See Margin.

- Earnings in the Annual Report: See Annual report.

- Overview: Cash flow and financial statement metrics: See Financial metrics.

Selective Income Metrics Purpose

Where Are They Used?

Net Income by itself is not always the most helpful metric for evaluating earnings. Potential problems with Net Income have to do with some of its revenue and expense components.

Remember that Income Statement Net Income is simply an instance of the income equation:

Income = Revenues – Expenses

In reality, Revenues and Expenses can mean quite a few individual items. For Net Income, these include normal operating expenses, of course. And, they also include expenses outside the firm's normal business. Expenses for Net Income may also reflect accounting conventions, taxes, and "unusual" losses. When present, these can "muddy the waters." These expenses can that is, distort the meaning of Net Income—at least for the firm's core line of business.

Consider, for example, how Domino's Pizza LLC presents earnings in annual reports. When discussing earnings, Domino's officers highlight EBITDA instead of Net Income. (EBITDA represents earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). Some shareholders no doubt ask: "Why EBITDA?"

Why Focus on EBITDA Instead of Net Profit?

Domino's business operates in the highly competitive "quick service restaurant" industry. For several years the company has pursued market and growth goals by adjusting its competitive strategy. As a result, management needs accurate feedback on how these changes impact earnings in their core line of business. In particular, they need earnings metrics that are precise. Precision is crucial because period-to-period changes of just a few percentage points can signal success or failure with strategic actions—the critical information for everyone with a keen interest in the firm's prospects for the future.

Domino's, however, has asset holdings, worldwide, which create large depreciation expenses from year to year. Also, the company and its franchise owners finance operations and acquisitions differently in different countries. Also, Domino's operates in many different tax jurisdictions. All this means that interest charges and depreciation expenses impact Net Income differently in different regions and countries. Also, Domino's operates in many different tax jurisdictions. All this means that taxes, interest, and depreciation impact Net Income differently in different regions and countries. Domino's, therefore, looks to EBITDA instead of Net Income for a more transparent, more accurate measure of earnings.

Bottom Line Net Income Still Matters.

All of the reasons for using "selective metrics" aside, however, it is still bottom line Net Income that determines a firm's legal responsibilities. Every year, for instance, companies must calculate and pay taxes. Directors must declare dividends and retained earnings. These actions deal with Net Income, not EBITDA.

Explain the Most Popular Earnings-Before Metric

Some are GAAP-Defined, Some Are Not

Selective Income metrics calculate from Income statement figures. Those familiar with the Income Statement should find that the names of individual "metrics" define themselves.

The table below lists and compares favorite income metrics from their contents.

GAAP-Defined Metrics vs. Non-Standardized Metrics

When comparing earnings metrics across companies, remember that some definitions leave room for analyst judgment or preference. Some "selective income" metrics, that is, allow analysts to decide, partially, what the "metric" represents.

- GAAP-defined metrics below offer the least flexibility of this kind

- Non-standard metrics provide flexibility. Non-standard "Earnings-before" metrics, therefore, should always carry annotations stating what the "metrics" include and what they do not include.

Selective Income Metrics

INCOME METRIC | INCOME METRIC INCLUDES... | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Op Rev & Exp | Tax Imp | Depr & Amort Exp | Int Exp Paid |

Non-Interest Financial income & Exp |

Non-Op Income & Exp Including Ext Items | |

| Net Income GAAP-Defined | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Operating Income GAAP-Defined | Yes | No | Yes | No | In some cases [1] | No |

| Earnings Before Taxes (EBT) GAAP-Defined 2 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) Non-Standard | Yes | No | Yes | No | Varies by user preference [3] | Varies by user preference [3] |

| Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization (EBITDA) Non-Standard | Yes | No | No | No | Varies by user preference [3] | Varies by user preference [3] |

| Earnings Before Extraordinary Items, Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization (EBEITDA) Non-Standard | Yes | No | No | No | Varies by user preference [3] | No |

Notes:

1. Revenues from interest earnings may appear in Operating income only if they represent the firm's regular business.

2. Earnings before taxes (EBT) results directly from GAAP-specified Income statement items. EBT is, therefore, "GAAP-Defined."

3. Different analysts can define the non-standard Income metrics, EBIT, EBITDA, and EBEITDA, are defined differently. Some choose to include financial revenues and extraordinary items in these metrics, for instance, while others prefer to exclude them.

Selective Income Metric

Operating Income

Operating Income, or Operating Profit, or Earnings from Operations represents company earnings from its core business. This metric shows the firm's earnings before adding revenues and expenses for extraordinary items, and before financial earnings or expenses (if the firm is not in financial services).

Operating Income is a GAAP-Defined Metric.

Operating income appears on the Income statement in currency units. Businesspeople often discuss Operating income results as operating margin, that is, as a percentage of Net sales revenues. Either way—as a margin or in currency units—operating income is appropriate for comparisons to competitors or industry standards.

Operating Income and Net Income Sometimes Send Opposite Messages

It is possible to report a positive Operating income and negative Net Income for the same period. This kind of "mixed message" from the Income statement typically occurs in periods with large, unusual expenses due to workforce reductions, natural disasters, or legal judgments. The same message can also result when a firm not in the financial sector declares investment losses or substantial financial expenses.

When Operating income and Net Income differ like this, expect the firm's officers to emphasize "Operating income" in the Annual Report.They do this to show that the company is performing well in its core line of business. They may also point to Operating income and argue that prospects are excellent, in spite of current losses.

Of course, companies sometimes report the reverse—positive Net Income along with negative Operating income. Here, extraordinary income "rescues" the firm's financial income. Firms can realize extraordinary or non-recurring income of this kind by selling real estate, other assets, or investment securities, for instance. Such situations call for serious concern, however, even though net profit is above zero. Directors, officers, and shareholders will want to know precisely why the core line of business is not performing well. And, they will ask leaders how they intend to improve prospects for the future.

Calculating Operating Income

Operating income before taxes normally appears under that name on the Income statement. The income equation defines Operating income as follows:

Operating Income = Net sales revenues

–Cost of goods sold (or Cost of sales, Cost of services)

– Operating expenses

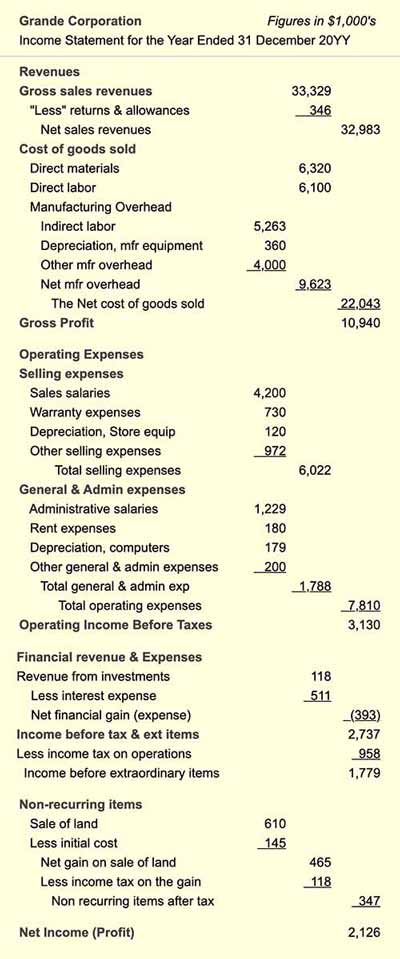

In the example below, Grande Corporation reports:

Operating income before taxes: $3,130,000.

Operating income after taxes on operating income: $2,172,000

Net Income after taxes: $2,126,000

Income Statement for Operating Income Input Data

This example statement shows only figures relevant to Operating income. A more detailed income version of the same statement appears at page bottom.

| Grande Corporation Figures in $1,000's Income Statement for the year ending at 31 December 20YY |

|

Revenues Extraordinary items after tax |

32,983 22,043 10,940 7,810 3,130 (393) 958 1,779 347 2,126 |

| Note: Usually, companies do not report "Operating income after taxes" as a line item on the Income statement. The figure calculates as follows: Operating income before taxes Less income tax on operating income only: Operating income after taxes |

4,732 3,130 1,096 2034 |

Operating Income: Pretax or After Tax Basis?

Operating income discussions usually refer to "pre-tax Operating income." They do so because pre-tax operating income regularly appears directly on the Income statement, while "after-tax operating income" does not.

The analyst who wants to find after-tax operating income starts with the pre-tax income figure and then takes two steps.

- Firstly, calculate the tax liability specifically for the pre-tax income figure.

- Secondly, subtract that tax figure from the pre-tax income figure.

The bottom three lines of the above statement describe the calculations. Note in this example that the "income tax" is the tax on "operating income" only. This result is not the standard Income statement line "Income tax on operations." The two can differ because the latter may include—as it does here—tax impacts of financial revenues and expenses.

Here, to find the tax on "operational income only," the analyst multiplies the marginal tax rate on operating income (here, 35%) by the before-tax operating income figure. Here, that tax is:

Tax on operating income only = 35.0% * $3,130 = $1,096

Selective Income Metric

Earnings Before Taxes EBT

Earnings Before Taxes EBT, or Pre-Tax Income, or Profit before taxes PBT shows--not surprisingly—company earnings before paying taxes. Pre-tax income is useful for comparing the earnings of companies in different tax jurisdictions.

A similar comparison occurs, for instance, when considering the salaries of individuals: two employees may have the same gross pay, but different after-tax income because they pay income taxes at different rates. Pre-tax salary figures show, however, that the employer pays both employees the same. Similarly, the pre-tax earnings metric is a more direct comparison of earnings between companies in different tax jurisdictions.

By the Income statement equation, Pre-tax earnings are:

Pre-tax Income = Revenues – Expenses (Except Tax Expenses)

In reality, the simplest way to calculate Pre-tax income from Income statement data is to start with "after-tax Net Income," and then add back all taxes. For example:

| Grande Corporation Figures in $1,000's Income Statement Figures for Calculating EBIT |

|

| Net Income (Profit) after taxes Plus income tax paid on operations Plus tax paid on extraordinary gains |

2,126 958 118 |

| Pre-Tax Income (Earnings before taxes) |

3,202 |

All Figures in the EBT example above are GAAP-defined. Therefore, EBT is GAAP-defined.

Selective Income Metric EBIT

Earnings Before Interest and Taxes

Earnings Before Interest and Taxes EBIT is another pre-tax income metric, slightly more selective than EBT(above). As the name says, EBIT represents earnings before considering tax and interest expenses.

- EBIT and EBITDA (next section) are popular with investment analysts, who must compare earnings from companies with different capital structures.

- Companies with a high leverage capital structure have higher interest expenses than companies with lower leverage. (High leverage means that lenders account for relatively more of the firm's funding than owners.)

EBIT measures income before factoring in interest. Therefore, EBIT provides a more accurate comparison of earning between companies at different leverage levels.

And, as with EBT, EBIT is also useful for comparing earnings of companies from different tax jurisdictions.

Important Characteristics of EBIT

Several essential characteristics of EBIT are as follows:

- EBIT is the same as Pre-tax net income, except that EBIT also excludes the contributions of interest expenses paid.

- EBIT usually (but not always) appears as Pre-tax income from operations as well as all non-operational income and expense (except for interest the firm pays). When analysts state EBIT in this way, the metric reflects extraordinary gains and extraordinary costs as well as depreciation and amortization.

- For companies not in the financial sector, EBIT excludes the impact of interest payments.

- GAAP does not define EBIT, and this means that EBIT reports may or may not include financial income and non-interest expenses.

Calculating EBIT

From the income equation, the EBIT definition is as follows:

EBIT = Revenues – Expenses (Except Tax Expenses and Interest Expenses)

When reporting non-standard metrics like EBIT, it is always good practice to state explicitly what the calculation includes. EBIT, for instance, should appear along with a note indicating whether or not financial or other non-operating revenues are present.

In practice, EBIT is more straightforward to calculate by starting with Net Income and adding back interest and taxes. With data from the example Income statement at page bottom, Grande Corporation's EBIT for the year is as follows:

| Grande Corporation Figures in $1,000's Income Statement Figures for Calculating EBIT |

|

| Net Income (Profit) after taxes Plus interest expense paid Plus income tax paid on operations Plus tax paid on extraordinary gains |

2,126 511 958 118 |

| EBIT |

3,713 |

Selective Income Metric EBITDA

Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation & Amortization

Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, and Depreciation and Amortization EBITDA, or Operational Cash Flow, is another pre-tax income metric, still more selective than EBIT. As the name suggests, EBITDA represents earnings before taxes, interest, depreciation, and amortization.

EBITDA, like EBIT, excludes interest and tax expenses. As a result, EBITDA also is useful for comparing earnings under these conditions:

- The companies have different capital structures. Different "capital structures" means they have different levels of interest obligations.

- The companies operate in different tax jurisdictions are therefore taxed at different rates.

EBITDA excludes everything that EBIT excludes, but EBITDA goes further also to exclude depreciation have amortization. These expenses can be substantial, and they can vary considerably between companies or even from year to year within one company.

These expenses, moreover, are "noncash expenses." In other words, these expenses do not cause real cash flow, but they do lower "Net Income." As such, they further distort the earnings picture from overall Net Income. By excluding depreciation and amortization expenses, EBITDA is immune to such distortions.

Important Characteristics of EBITDA

Note especially the following about EBITDA:

- EBITDA is sometimes called "Operational cash flow." EBITDA has this name because it excludes depreciation and amortization (noncash flow expenses),

- GAAP does not define EBITDA. It is thus a non-standard metric.

- Some analysts choose to include only operating revenues and expenses in the metric. Those analysts claim that EBITDA and Operating income are the same metrics. They may even use the two terms interchangeably.

- Others believe the definition should include financial revenues and expenses (other than interest expenses), as well as non-operating costs including extraordinary gains and losses.

- Equating EBITDA and Operating income is a risky, at best, because GAAP includes depreciation in operating income, whereas EBITDA by definition does not.

- Note, however, that analysts who do allow financial and non-operating revenues and expenses into EBITDA do not see operating income and EBITDA as the same thing.

Defining EBITDA

Using the Income statement equation, EBITDA represents:

EBITDA = Revenues

– Expenses (except expenses for taxes, interest,

depreciation, and amortization)

Example Calculating EBITDA

In practice, EBITDA is more straightforward to calculate by starting with Net Income and adding back interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization expenses. The following example uses data from the example statement below.

Grande Corporation EBITDA for the year calculates as:

| Grande Corporation Figures in $1,000's Income Statement Figures for Calculating EBITDA |

|

| Net Income (Profit) after taxes Plus depreciation expense, store equipment Plus depreciation expense, manufacturing equip. Plus depreciation expense, computers Plus interest expense paid Plus income tax paid on operations Plus tax paid on extraordinary gains |

2,126 120 360 179 511 958 118 |

| EBITDA |

4,732 |

Here, EBITDA ($4,372,000) exceeds Operating income ($3,130,000). Thus, operating EBITDA are not always the same. Here, they differ for two reasons:

- Operating income reflects depreciation expense, while EBITDA does not.

- Also, the analyst chose to include non-operating revenues and expenses in EBITDA, whereas they are usually absent from operating income.

Selective Income Metric EBEITDA

Earnings Before Extraordinary Items, Interest, Taxes, Depreciation & Amortization

Earnings Before Extraordinary Items, Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization or EBEITDA is undoubtedly the most selective of the income metrics described here.

EBITDA is Not Standardized by GAAP

Note that GAAP does not define EBEITDA, making EBEITDA another non-standard "earnings-before" metric.As with other non-standard measures, merely naming the "metric" does not fully specify what it represents.

When is EBEITDA Just Another Instance of EBITDA?

To some, EBEITDA seems like another instance of the slightly less selective metric, EBITDA. That view is possible because EBEITDA and EBITDA differ on only two minor points.

- Firstly, the analyst may choose whether or not to include extraordinary items in EBITDA.

- Secondly, EBEITDA by definition excludes extraordinary items.

EBEITDA and EBITDA are therefore the same when EBITDA excludes extraordinary items.

Otherwise, EBEITDA serves a unique role in its own right. EBEITIDA and EBITDA are different metrics when both of these conditions apply:

- An EBITDA metric is also in view

- The EBITDA metric includes large extraordinary items

In such cases, analysts see EBEITDA (rather than EBITDA) as the more accurate measure of earnings in the core line of business. Analysts designate EBEITDA is more accurate because it explicitly excludes extraordinary items.

Example Income Statement

Data Source for Selective Income Metrics

Example calculations above use data from the sample Income Statement Below. This statement represents a manufacturing firm. However, the structure and contents are similar across a wide range of industries.