The Special Nature of the IT Business Case

IT ROI figures still fail to “come true” and still raise cries of “Soft Benefits!"

Solution Matrix Ltd works with CIOs, IS/IT directors, managers, and financial executives in a wide range of industries and government settings, all of whom have a need to understand and communicate the business value that results from IT actions and acquisitions. Below are several practical findings from 20 years experience with IT business issues: proven principles and tactics for building-in credibility, accuracy, and practical value into the IT business case.

Start with a working definition for IT Business Case.

Define Information Technology Business Case

The IT Business Case is an analysis that delivers two kinds of information about the likely consequences of an IT acquisition, project, task, or decision:

- Forecasts. The business case asks "What happens if we take this or that action?" Case results answer in business terms: business costs, business benefits, business risks.

- Proof. Reasoning and evidence make the case for choosing one IT action over another. The case proves in compelling terms why one course of action is the better business decision.

Your Business Case Must Score High in Credibility

IT professionals turn to business case analysis for a wide range of reasons. Some need funding for specific projects or acquisitions, while others aim to secure high-level buy-in for strategic decisions. Some simply need to justify their stewardship of IT funds over the last few years, or show on the record that they follow policies and best-practice decision-making. What they have in common is a need to build an accurate, credible IT business case.

Most approach the business case project expecting a positive ROI and other favorable outcomes from actions they propose. Very few start out expecting to show a net loss. Most do report frustration in trying to “sell” previous proposals inside their organizations. Few are truly comfortable with their ability to estimate IT costs and benefits in advance.

A short list of what it takes to produce a good IT business case holds few surprises:

- The business case author must be:

- Thorough (track down all possible impacts, costs, and benefits),

- Clear and logical (articulate the cause and effect chain that leads to each cost/benefit impact)

- Objective (unbiased, including everything that is material, good or bad)

- Systematic (have good models and rules for finding and summarizing values).

- Financial talent also helps as does a solid grasp of the interplay between IT capacity, service levels, user needs, and IT resource requirements.

Intelligent managers appreciate this much already and—as you know if you’ve heard from the IT consulting community lately—the market is awash with methods claiming these virtues. Nevertheless, IT ROI figures still fail to “come true,” still raise cries of “Soft Benefits!” and fail to instill confidence in senior management. Why? What can IT managers do about it?

Nine Keys to IT Business Case Success

Following are nine proven concepts and methods that are usually critical for building and delivering a successful IT business case. If you have ever proposed an IT investment and then failed to gain approval or failed to deliver expected returns, you may find here just what was missing.

The nine keys below can work well with most good approaches to business case building. They are especially applicable, however, with the business case structure and content in the online article Business case and in the PDF ebook Business Case Essentials.

Contents

- The special nature of the IT business case.

- Key 1: Recruit and use a Reference Group .

- Key 2: Agree on the cost model for the IT business case.

- Key 3: Include all the benefits.

- Key 4: Value every critical IT benefit in financial terms.

- Key 5: Understand the difference:

- Key 6: Put your analysis into the long-term view.

- Key 7: Measire and present risks and uncertainty.

- Key 8: Keep nonfinancial benefits in view.

- Key 9: Use case results for management and control.

Related Topics

- The article Business Case provides a complete introduction to business case analysis and the process for building the business case.

- For a more in-depth introduction to the IT business case, including numerical examples, see the ebook Business Case Essentials.

IT Business Case Key 1

Recruit and Use a Reference Group

Don't Do It All Yourself

If you are preparing a business case for your management, and your organization is the primary beneficiary of the technology action, it is tempting to take sole responsibility for building the evidence that will justify it.

- It is tempting to have your staff find all the costs and benefits, give yourself the job of adding up their cost/benefit lists, and then present the results to your manager or the Capital Review Committee.

- If you are a consultant building the case for a client, it is also tempting to do the case yourself—to be sure it comes out "right" and to highlight your expertise and value.

There are serious risks, however, in the "solo" approach to building an IT business case.

The basic problem for the IT case-builder has to do with the nature of information technology in business today: IT is integral to almost every functional area and IT actions have financial consequences that cross boundaries of all kinds: organizations, management levels, budget categories, planning periods.

All of this adds to the reasons for recruiting and cultivating a cross-organizational, cross-functional Reference Group to help you design the case and establish credibility. Notice that the Reference Group is not the project team that does the hard, time-consuming work digging into databases, interviewing experts, analyzing workflow in detail, and so on. It is an advisory group that also provides liaison with other parts of the larger organization. In some settings, business case Reference Groups carry names such as Review Committee, Validation Board, Steering Group, or something similar..

When recruiting a Reference Group, try to include IT users and their managers, senior financial managers and, if possible, other high-level executives directly responsible for the company’s financial performance. Look especially for senior managers in organizations and functions outside your own that will feel impact by the subject of your proposal: these people are genuine stakeholders. Also, try to include subject matter experts in areas relevant to the case, such as accounting, finance, human resources, or strategic planning.

Add Authority and Credibility and Spread the Sense of Ownership

A solid, well-handled Reference Group can contribute to the success of your IT business case in several ways. These groups normally meet 3-5 times in the course of the case-building project. The first kind of team contribution is evident to all:

Add Authority and Credibility

The Reference Group will help fill in the cost and benefits models with line items and ideas you might otherwise overlook, or might be outside your own areas of knowledge. The team can also bring other critical expertise and information to the table. Their contributions add authority and credibility that will be difficult to achieve if you “do it yourself.” For instance:

- Line managers on the team can help “cost” and “value” the operational impact of IT actions in their areas (manufacturing, procurement, marketing, sales, customer service, facilities, shipping, etc.).

- A financial expert can help connect the IT business case with the organization’s long-range business plan—a great aid to “sizing” IT contributions to expected business benefits.

- A Human Resources expert can help identify and gauge the “people costs” of the action: job levels, salaries, overhead, training requirements, hiring and relocation, and so on.

- High level managers should be able to help prioritize, legitimize, and assign a value to any IT contributions to the organization’s strategic business objectives.

That much of the Reference Group role is obvious. Some other functions for the team are less obvious at first, but equally valuable.

Spread the Sense of Ownership

The Reference Group can serve to spread a sense of ownership for the business case. Those who take part in case-building naturally develop a sense of ownership for it. In meetings and discussions, as team members contribute to case design and development. Inevitably, it becomes their case coming up for review as well as it is yours. That is an advantage for you, because most people do not want something they work on, and own, to fail.

Communicate Rationale and Expectations for Outcomes

In most situations, the IT business case will undergo critical review, either by an individual or by a review committee. In competitive or critical settings, you do not want to have to announce, explain, and defend your methodology, assumptions, and business case results to reviewers all at the same time. With an active Reference Group, you can communicate and agree methods and assumptions widely, well before reviewers evaluate case results. That should, at least, avoid unexpected criticisms of these factors at the actual review.

By opening the communication channel during case building, before delivering the final report, before the final results, Reference Group members can also help set expectations for the business case results and establish the rationale that legitimizes benefits for the case (see Key 3 and Key 4 below). When review day comes, critics may still argue your interpretation of case results, but you leave them little room to question your methods, data, or rationale late in the game.

Provide Access to People and Data

If the IT action in your business case has cross-functional, cross-organizational impacts (and most IT actions do), you will very likely have to check assumptions, research impacts, and gather data from sources outside your organization. Reference Group members can help “open doors” and direct you to the right people in their organizations who can provide that information.

Handle Criticism and Critics

Finally, you may be able to use the Reference Group as a tool for handling people who are severe critics of your proposal. If you face people who fit that description, it may be advisable to bring one or more of them onto the Reference Group at the outset.

The critical word here is "may." You must judge the wisdom of taking this step, using your knowledge and familiarity of the individuals in question. As members of the Reference Group, they will object and contribute everything they have to say before the final review, assuring them that their positions are “on the record.”

IT Business Case Key 2

Agree on the Cost Model for the iT Business Case

Expect the Cost Questions

You may be writing the IT business case to request a new hardware or software system. You may be writing to propose an infrastructure upgrade, migration to a new operating environment, or some other action. Regardless of the case subject or purpose, however, those who review the case are no doubt aware that IT actions are famous for bringing so-called “hidden costs.” You can expect critical cost questions like these:

- How do we know the business case includes all the costs we will incur over the next few years?

- How do we know that we are comparing alternate action options fairly?

- How do we keep the lifetime costs of this investment under control? How do we avoid unpleasant cost surprises later?

A good IT cost model for the business case will help you address all three kinds of questions. In fact, one of the first tasks for the case-building team should be to design and agree on the structure of the cost model. A useful first task for the Reference Group is to complete and approve the cost model for the business case analysis.

The cost model is critical because the link between technology and specific costs (and benefits) is often unclear or hidden, and because you need a rational system for deciding which cost items belong in the business case and which do not.

Build a Cost Model With Self-Evident Completeness

Model Objective: Be Complete

The first purpose of the cost model is to help the case builder and Reference Group identify all relevant costs for the case. The goal is to bring everyone to high comfort level that the cost side of the analysis is complete.

A good cost model shows every possible place to look for material cost impacts of the IT action. It clarifies which items and data to omit, as well. Should your IT business case include the cost of user training? Should it cover outside consultant fees? You won’t have to anguish over a response if you have already a cost model that is clear, appropriate, and unquestionably complete.

Model Objective: Communicate Completeness and Fairness

The second purpose of the cost model is to communicate completeness and fairness to all who read and use the case.

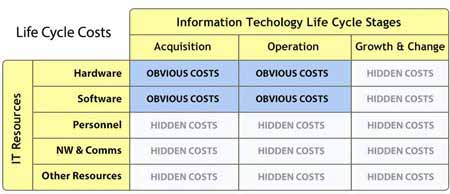

When a model’s completeness is self-evident, and its boundaries are clear, it becomes a vehicle for assuring others that you have been complete, and your case is free of personal bias in deciding what to include and what to exclude. For the cost model example in Exhibit 1below, completeness should be self-evident: Anyone familiar with the IT proposal should be able to judge the selection of categories on both axes and agree that each axis covers all relevant cost types for that dimension.

When the business case compares alternative IT actions, the cost model can also demonstrate clearly that the analyst is comparing costs in different action scenarios fairly. The analyst uses the same cost model to identify cost impacts in all scenarios. If the choice of cost categories for the model unfairly favors one alternative over another, that bias should be more evident to all in the cost model structure than from a simple list of cost items.

Your IT business case may include hundreds of individual cost items, but you should be able to sketch the cost model in simple terms and use it to demonstrate that all the relevant cost categories are present.

Build the Model, Identify the Costs

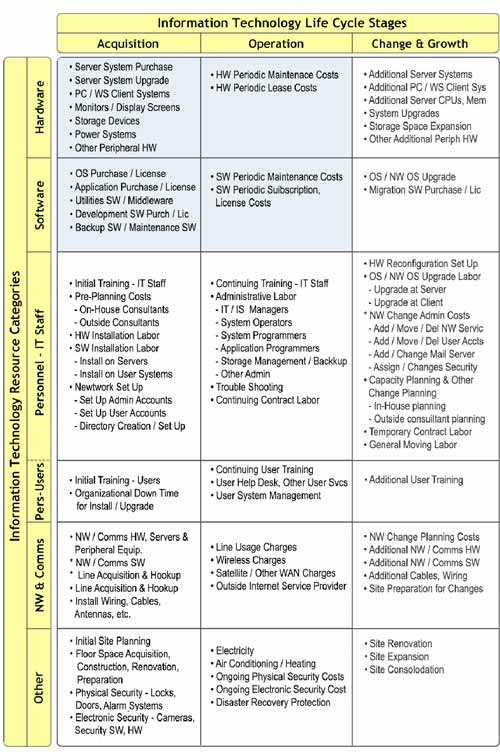

Exhibit 2 below is a more detailed version of the cost model in Figure 1. This example, in fact, is a representative IT cost model that has proven very useful across a wide range of industries and IT actions. It is a resource-basis cost model because it shows us all IT cost impacts within resource classes.

This example is an instance of resource-basis cost modeling because the vertical dimension of the model matrix presents all of the IT resource categories that need cost estimates.

- Hardware

- Software

- Personnel labor (here divided into sub-categories, “IT Staff” and “Users”)

- Networking and Communications

- Other Resources.

Note that column headings also represent cost categories. The model organizes the horizontal dimension with cost category names for significant IT lifecycle events or stages:

- Acquisition and Implementation

- Operation

- Ongoing Change and Growth Costs

A cost model built this way is nothing more than a two-dimensional list of all possible cost impacts. The key to its value is in the organization: cost items within each cell have a relationship to each other. Items within a single cell are generally costs that change together, and most likely have common cost drivers. For that reason, managers will usually plan and manage items within a cell together .

The cost model in fact, can capture total cost of ownership (TCO) for the IT action, across a multi-year life cycle period. The model includes categories that capture the more obvious IT costs (such as HW and SW acquisition) as well as IT cost impacts that are real but less obvious, or "hidden" (such as the full range of personnel costs, or ongoing growth and change costs).

Agree Early on the Cost Model

The cost model sets the rules for which costs belong in the case and which do not. The cost model design, therefore, should be complete before anyone on the case-building team tries to project cost or benefit consequences. Once the subject, purpose, and scope of your case are defined, priorities on the case-building team should turn to cost model design.

When the case-building team agrees on the appropriate rows and columns for the model and begins to identify some of the cost line items, the Reference Group should meet to suggest any adjustments they feel necessary, then agree and approve the design for the business case.

Use the Cost Model for Management and Control

Another purpose of the cost model is to provide a vehicle for cost analysis, cost management, and cost control. The model provides a basis for analyzing IT spending, by giving answers to cost questions that are difficult to address with the scenario cash flow statements in the business case.

As soon as the cost model structure is in place, the analyst can begin projecting actual cash flow estimates for each cost item, across the business case analysis period. For IT cases, this usually means a period of 3 to 5 years into the future. The scenario cash flow statements will show how cost and benefit projections come together across this time span, but the cost model itself provides another view of future spending that can be very useful for managing and controlling costs.

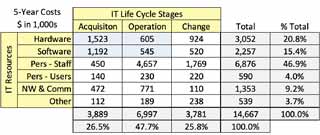

Besides putting the cost estimates into cash flow statements, we can also fill in the cells of the cost model with the total 5-year (or 3 or 4-year) spending forecast for the items in each cell and then create totals for each cell, each row, and each column. Table 2 (below), for instance, shows one company’s five-year cost estimates for an IT infrastructure upgrade, with cell totals and marginal totals.

Bringing marginal totals into the picture adds to the model’s value as a tool for financial control. Here, marginal totals show costs by IT resource axis category (vertical dimension) and life cycle stage (horizontal ). Several messages from Table 3 stand out. “People costs” (IT Staff and IT Users together) make up 48.5% of the 5-year cost picture, for instance. Post-acquisition costs make up 73.9% of the total cost story.

When planning such a move, the natural temptation is to focus on Hardware and Software acquisition and operation costs (the four cells in the upper left corner of Table 2). Real cost control, however, depends on understanding the implication of these choices on the other cost impact areas, the so-called “hidden costs” of computing.

For examples and more on building and using the IT cost model, see Business Case Essentials.

IT Business Case Key 3

Include All Business Benefits

There is More to Life Than Cost Savings

Usually, the easiest IT benefits to find, quantify, and defend, come from cost savings and avoiding costs—benefits that appear when comparing the cost analysis under a proposal scenario to cost analysis under a business as usual scenario. These kinds of benefits usually result from several ways of using IT resources. The most significant business benefits from an IT action, however, often lie elsewhere.

When searching for potential business benefits from an IT action, it is helpful to keep two ideas in mind:

First, Benefit in business analysis means an outcome from an IT action that contributes towards meeting a business objective of the organization. Reaching goals has value. IT actions without a clear business objective in mind does not necessarily have value.

Secondly, when an IT professional first proposes an IT action, the proposal should:

- Identify specific business objectives proposal addresses.

- Explain how to measure progress towards these goals.

- Sate target levels to achieve.

There are at least four ways the outcomes of IT actions can contribute to meeting business objectives, and thus qualify as the business case "benefits":

- First, the IT action outcomes may improve efficiency. Efficiency means either (1) accomplishing specific work at less cost, or (2) increased productivity, i.e., achieving more at the same value.

- Second, the IT action outcomes may improve the quality or effectiveness of work. This result could be, for instance, improving customer service delivery, product design quality, or advertising effectiveness.

- Third, the IT action outcomes may enable people or organizations to innovate, that is, engaging in valuable activities they were not able to do before.

- Fourth, the IT action outcomes may reduce risk (e.g., lowering the risk of service unavailability, lowering the risk of employee accidents, or lowering the risk of losing a competitive advantage).

With these two ideas in mind, IT management and IT users are prepared to search for and identify the full scope of potential business benefits from a proposed IT action.

Whose Costs and Whose Benefits Belong in the Case?

Consider the "audience scope" of the case carefully that is, specifically whose costs and whose benefits belong in the case. Audience scope is an issue you must raise, discuss, and settle with your business case reviewers before presenting the final results. In any case, the appropriate range of beneficiaries might deserve to be more extensive than you initially think. :

- In many IT business cases in government, the case developer has a mandate to consider benefits to a population that the organization serves, as well as cash inflows and outflows to the IT organizations and agencies involved.

- IT actions in an extensive health care delivery system may have impacts far beyond the IT organization. The work may bring improvements in efficiency and accuracy of billing, and record handling may improve throughout the system, professional service delivery may be better or more timely, the range of services may be more significant, system-wide operating costs may be lower, staff professionalism may be improve, and so on..

There is no question that IT actions can have beneficiaries beyond the IT organization. However, it is the case developer’s responsibility to extend the scope of beneficiary coverage appropriately, by agreement with case audience or recipients. Reference Group members can play a critical role in reaching this kind of agreement. The crucial point is that beneficiary scope is not set automatically by defining the subject of the case. Nor does the cost/benefit analysis itself determine where to place the boundaries of coverage.

Don’t Omit a Benefit Because It Is Hard to Quantify

Using the above characterization of IT action benefits, the case builder must judge which benefits to include and which to exclude from the IT business case. Some "Dos" and "Don'ts" in this regard include the following:

- Do not omit a benefit from the business case just because it is hard to quantify.

The goal is to quantify beneficial outcomes, either as financial outcomes or as "tangible" non- financial incomes (e.g., concerning impacts on measurable key performance indicators).

It may be difficult in some cases to reach agreement on acceptable quantitative measures of the benefit, but if the outcome indeed contributes towards achieving a vital business objective, it belongs in the case. - Do not omit nonfinancial benefits merely because you cannot give them economic value.

An IT outcome may contribute towards meeting a vital business objective that first appears in nonfinancial terms. Businesses often define and measure goals for customer satisfaction improvement, or branding, or lower risk, for instance, in nonfinancial but essential tangible performance indicators. IT action outcomes that contribute towards meeting these objectives are legitimate benefits for the case, even if they must appear without receiving financial value. - Do omit a benefit if it is unlikely or its probability is unknown. If the best you can say is that an outcome "might" contribute towards meeting a business objective, do not include it in case. The presence of "weak" benefits can make the entire case look weak.

IT Business Case Key 4

Value Every Critical Benefit in Financial Terms

Which Business Objectives Does the Benefit Address?

If you assign no financial value to an agreed benefit, that benefit contributes nothing to the economic analysis. Is this appropriate? Often it is not. The company may invest in technology to improve its professional image, improve customer satisfaction, or create a more professional work environment. But how much credit do these benefits deserve in real money? They will contribute 0 to the case financial summary if an acceptable valuation is not agreed.

Consider, for instance, a few strategic objectives at a large commercial bank:

- Increase market share

- Increase revenues

- Move business into more profitable financial services (i.e., change the business model)

- Decrease loan losses

In a large bank, these objectives refer to substantial cash flow streams. If an IT investment improves performance in any, even by just a few percentage points, the benefits of the IT investment can be massive. A small fraction of a considerable number is itself a large number.

Nevertheless, a bank IT director may attempt to cost-justify the investment solely regarding cost savings and cost avoidance (displacement of data entry clerks, for instance, or lower expected hiring rates). The latter benefits are smaller but more accessible to quantify. A good IT business case needs all substantial benefits of both kinds, but often, the significant strategic benefits fall to criticism and get left out. Top-level management may be reluctant to credit IT for reaching strategic business objectives, because IT alone may not guarantee the goal.

A new network architecture for the bank might help reduce loan losses or help sell more profitable financial services (perhaps by providing timely access to critical customer data), but it is not the only requirement for reaching these objectives. Reducing loan losses may also require changes in the way the bank trains and manages professional staff, or changes in loan decision criteria, for instance. However, if the IT action is necessary for reaching the objective, or if it undoubtedly contributes to getting there, IT deserves some of the credit in the business case. That credit will not show up in the case financial summary unless the worth of the contribution appears in monetary terms.

Tactics for Assigning Financial Value to Benefits

Not every benefit will be quantifiable to everyone's satisfaction, but some proven methods often work to produce an acceptable value. There is not space to cover these methods here1 but, in a nutshell, many of them rely on strategies for:

- Quantifying the worth of the benefit’s effects. For example, a “more professional work environment” (the IT action outcome) may have a highly quantifiable impact on such things as employee turnover—regarding recruiting costs, training costs, and productivity.

- Using a value that is equal to the cost of alternative solutions. For instance, a commercial bank loan officer must have access to customer credit histories and other business and economic data. Technology brings that information to the desk within a few minutes. What is the value of that IT benefit? Consider the cost of the next most cost-effective means of getting the same results.

- Setting the value equal to the cost of not providing the benefit.

Do everything you can to quantify every essential benefit in financial terms, but include only those that you or your audience can accept with confidence.

IT Business Case Key 5

Understand Full Value vs Incremental Cash Flow

"Savings," "Improvements," and "Increases" are Relative Terms

IT business case builders sometimes stumble when they questions like these turn up:

- Where does a cost-saving go in the cash flow summary for the business case? Is it a positive inflow appearing under “Benefits”? Or is it simply a lower cash outflow under “Expenses”?

- How should you measure improvements in the IT business Case? If engineering productivity should improve by 30% with a new software design system, where does the case capture the improvement?

- How should increases enter the business case? If a new Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system should lead to sale revenues increases of, say 20%, where do we capture those increases? Do we include the likely new sales revenue figures? Or do we add just the addition?

Many organizations undertake IT actions to save money, improve productivity, or increase sales. Notice that "saving," "improving," and "increasing" are relative terms. We have to ask: “Savings, relative to what?” Improvements, or increases, relative to what?

The “what” is a baseline scenario, which we call “Business as Usual” (Other case builders may use the terms “As Is” and “To Be” to distinguish between “Business as Usual” and Proposal scenarios). In any case, savings, improvements, and increases will only show up as such if we have two scenes to compare.

Knowing how to compare two business case scenarios, moreover, requires an understanding of the difference between incremental and full value cost and benefit projections.

Incremental vs. Full Value Cash Flow Projections

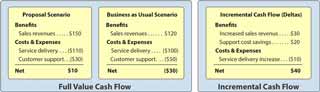

Consider the two simple cash flow scenarios shown at left and center in Exhibit 3 (below). Each represents a different business case scenario, "Proposal," or “Business as Usual.” These are full value scenarios showing the actual total cash flow values for each Benefit item and each Costs & Expenses item. Sales revenues under the Proposal, for instance, appear at its full value, $150.

At the right is an "Incremental" scenario, which shows only the differences or "deltas" between the two full value scenarios. The analyst calculates the sales revenue delta, or increment as follows:

Sales Revenue Increment

= Proposal Rev – Business as Usual Rev

= $150 – $120 = $30

From these projections, it appears there will be cost savings in "Customer support" under the "Proposal" scenario. How does the business case author identify and communicate the savings?

- One approach is to present both full value scenarios (at left) and describe the differences between corresponding line items on both "full value" statements. We can see, for instance, that customer support costs are $20 less under the Proposal Scenario. In the Net cash flow figures at the bottom, we can also see that “Business as Usual” is losing money right now, whereas the Proposal scenario looks forward to a net gain.

- The case builder can also lead with a different presentation, however, as shown in the deltas at right, namely, the “Incremental” approach. Here, the data for each line item show only the proposal differences, or increments, from business as usual. The customer support delta calls for subtracting a larger negative number from a smaller negative number, giving a positive result:

Customer Support Increment

= Proposal C Support– Business as C Support

= ($30) – ($50) = $30

Many people (including your case audience) may look at the full value approach and an incremental approach and say “What’s the difference? Don’t both approaches say the same thing?” In fact, they do say the same thing but they convey the message differently.

Failure to appreciate the difference is the cause of many business case confusions. One confusion, of course, is the question of what to do with cost savings: Do they go under “Benefits” or “Costs & Expenses”? More pervasive, however, is the problem of mixed data: case builders often err by including full values for some line items and incremental figures for others in the same cash flow statement. This mistake is so easy to make that it is always wise to review your cases or those of others to be sure that all data are one kind or the other.

Which Approach Should You Lead With?

Which approach is more appropriate for the IT business case? First, remember that you will have to create both full value scenarios even if you are going to lead your presentation with the incremental approach: the "Incremental" deltas derive from the "full values," after all.

When discussing business case results, however, a discussion referring to the full value data is better when:

- The case primarily serves budgeting or business planning purposes. Here, the analysis must show the total magnitudes of line item numbers as well as the difference between scenarios.

- There is no viable “business as usual scenario,” or there are many different proposal scenarios to compare.

- The “cost” side of the cost/benefit case will go into a “Total Cost of Ownership” analysis of its own.

On the other hand, the incremental approach is the more appropriate focus for discussion when:

- The action scenario is essentially an investment decision, and management truly wants to weigh net costs and net returns of the action itself, independent of other financial factors in the environment.

- The incremental costs and returns of the action are small relative total inflows and outflows.

IT Business Case Key 6

Present the Long-Term View

Visualize the Timeline

Anyone reviewing an IT business case analysis of any kind, it is prudent to look immediately for several crucial business case elements. Essential elements include a clear statement of case subject and case purpose, the complete cost model for the case, the rationale for valuing benefits (if the business case includes benefits), and a timeline.

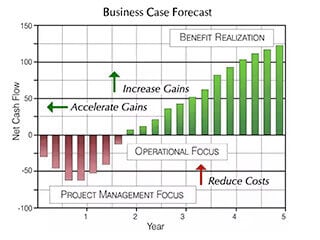

The case-builder may know very well when specific inflows and outflows occur, or when the net impact reaches a "break even" point. But, the case audience and stakeholders also need to see how these eventsoccur in time, to judge the validity of results and to know best how to apply financial tactics during implementation (reduce costs, accelerate gains, postpone expenses, or increase profits).

How Long is Long Enough?

What is the most appropriate analysis period? Significant IT actions usually have cost and benefit consequences that extend across years, sometimes long after the original hardware and software purchases have been written off and replaced.

When an organization chooses a new operating system or a different database architecture, for instance, the choice may limit or direct IT planning options through several cycles of CPU upgrades or software versions, a period of an impact that covers 3-5 years at least.

IT Business Case Key 7

Measure and Present Risks

Uncertainty is Certain

Business case results are always uncertain to some degree because they project events into the future. They are estimates based on other estimates: IT cost projections for the next several years may derive from capacity growth forecasts, transaction volume estimates, and likely future prices, for instance. benefit forecasts may reflect business performance forecasts, likely market changes, and future competitor actions--all of which depend on other factors.

When you present business case results, your audience—customer, client, or management—will very likely have questions like these:

- What are the chances of seeing other results besides your main predicted outcome?

- What are the risks to achieving these results?

- What can we do to maximize the results?

A standard approach is merely to set higher hurdle rates or require shorter payback periods for proposals under consideration. When decision-makers take this approach, however, without an eye on the individual risk components, the accuracy of the business case and the ability to control risk suffer.

Measure the Risks

The business case for entering a new product market projects a net gain of $590,000 over the next five years. Everyone knows, however, that the real result will not be $590 thousand, exactly: it will be something more or something less. But can the business case builder say anything more about the likelihood of other results? Here is one kind of response to that question.

Risk management methods are beyond the scope of this paper, but we can point out here why that case-builders benefit from learning and using well-proven approaches, risk analysis using Monte Carlo simulation. In a nutshell, Monte Carlo asks you to do the following:

- Identify the critical “input” factors (variables) that impact bottom-line results

- Assign minimum and maximum possible values to each input factor

- Describe the likelihood the variable will have different values between its minimum and maximum (in statistical terms, describe the probability density function for the input variable).

Monte Carlo’s primary output is a probability “curve” such as Exhibit 6 (below) that lets the business case author make statements like these:

- “We have a 90% chance of realizing a net gain of at least $329,300."

- We have a 50% chance of earning at least $500,000 and a 20% chance of gaining $750,000.”

- The 80% confidence interval for likely gains is $329.30 - 7889,500.

Should management trust that estimate? Remember, these decision-makers are highly risk-averse. They will go forward only if they have confidence in the projections. If the cost of labor turns out to be more than $500,000 the service becomes unprofitable. How likely is that?

This kind of simulation results may provide the "comfortable certainty" decision-makers need before trusting the IT business case recommendation.

Sensitivity Analysis: What happens if Assumptions Change?

With or without this kind of risk analysis, however, every business case, however, deserves some form of sensitivity analysis, even if very minimal—perhaps nothing more than a set of best case/worst-case scenarios. Sensitivity analysis asks the question: “Which assumptions or input data are most important in controlling overall case results?”This question is equivalent to asking: Which factors are most important in controlling bottom-line results?

Monte Carlo simulation tools that produce probability estimates (such as Exhibit 6) can also address sensitivity, or "control" questions. Simulation methods do this by measuring statistical correlations between different values of input assumptions, and output values for business case forecasts. The sensitivity analysis, for example, could compare correlations between input factors such as "expected inflation rates," "price changes," and "salary increases" on the one hand, with forecasts for an output factor such as "total cost."

When presenting sensitivity results for different input assumptions, you can make the case results more useful dividing significant risk factors or dependencies into two groups:

- Those completely outside your control

These might include such things as the rate of inflation, competitor’s actions, foreign currency exchange rates, natural disasters, acts of war, or government regulation. These factors need watching/

Management intervention (changes to the implementation plan) may be called for if these factors change in a way that puts the predicted results at risk. - Those which you can influence or control to some degree.

These might include such things as skill levels of your professional staff, timely completion of related projects, achieving cost control goals, recruitment and hiring of key individuals, and many others. These factors need constant management attention.

IT Business Case Key 8

Keep Non-Financial Benefits in View

You May Not Succeed in Giving Financial Value to Every Benefit

No matter how hard you try to put a value on every IT benefit (Key 4 above), some will probably remain unquantified, at least in financial terms. Such benefits may include improvements in corporate image, customer satisfaction, or employee morale. These may represent primary corporate objectives, and reaching them will no doubt translate into lower costs and increasing revenues. Nevertheless, you and your audience may not be ready to accept monetary estimates for them with confidence. These benefits will not enter the business case financial summary or cash flow statements, but they may still deserve consideration in the proposal.

If you cannot put a financial value on beneficial impacts, should you say anything about them? We recommend answering "yes" if these conditions conform to your satisfaction. The effect:

- Is likely

- Contributes to a vital business objective

- Is large enough to matter

Do Not Omit Real Benefits, Even Nonfinancial Benefits

For nonfinancial benefits that meet these criteria, here are some brief guidelines on how to use them effectively in the IT business case.

Make the Impact Tangible

Show how to observe, verify, and measure the benefit in tangible terms--even if not monetary terms. You may expect a real “improvement in staff professionalism,” for instance, that is not easy to evaluate in monetary terms. You can, however, describe the likely effects of that benefit in other observable terms, such as lower staff turnover, easier recruiting, less absenteeism, or the appearance of the workplace to customers or clients.

Connect Impacts with Business Objectives

Ideally, the case report Introduction presents the business objectives, opportunities, or problems that the case subject address. When you identify tangible nonfinancial benefits of your proposal, connect them directly to this introductory material, especially under “Conclusions and Recommendations” in the business case report or presentation.

Make the Point: A Benefit has likely Financial Benefit, Even when the Value is Not Easy to Estimate Precisely.

By taking these steps, you remind your case audience and stakeholders that business decisions should reflect more than a simple comparison of financial sums.

IT Business Case Key 9

Use Case Results for Management and Control

Improveme With Experience

No matter how well you prepare your first IT business case, your next case will probably not be your best one. The one after that will probably be better—easier to understand,, more accurate, with practical guidance that is more accessible. Case-building improvements over time require individual and organizational experience

From repeated trials over time, you will learn how best to refine the cost model and how to assign cost and benefit values to IT actions appropriately for your situation. By consistently using the same approach to business case design, over time, your organization should improve its ability to understand and use case results effectively, and with confidence. Unfortunately, many people and many organizations have to begin each case-building project starting from 0.

Validate Costs, Benefits, and Assumptions

One way to learn from experience—and establish a consistent approach to case design and case methods—is to use the case as a financial control tool throughout the lifetime of its subject. The business case that justified an IT acquisition or action can live on, long after the initial decision, as the heart of a powerful tool for managing the consequences of that decision. Expected cash flow items and other elements can be linked into a dynamic business model for tracking, controlling, and measuring IT costs and benefits.

Some specific goals for using the case this way include:

- Validate Assumptions.

Cost and benefit cash flow estimates derive from assumptions—many assumptions in some cases—about such things as future labor costs, business volume, transaction volume, service provider prices, insurance premiums, and so on.

As time progresses, these will almost certainly change from the values assumed when business case results first appear. Regular updating of the assumptions underlying cost and benefit estimates will keep cash flow projections more accurate.

- Validate Cost Model Structure and Content (see, for example, Table 1).

You will want to pay attention to questions like these: Do cost line items in the same cell, in fact, change together? Does management plan these items together? Are some rows and columns of the model so insignificant that they can be dropped or merged with others? Are there significant cost categories missing from the original model? - Validate Costs.

Where there is a gap between prediction (the business case) and actual results, ask if the estimate drew upon faulty assumptions (e.g., an assumed need for storage capacity) or whether the costing of that resource was off the mark (e.g., not anticipating hardware price changes). -

Validate Benefits.

Pay attention especially to the timing of benefits and their actual arrival. Was everything online and running as planned? Did productivity “ramp up” as expected?

Of course, the analyst will adjust specific figures as plans turn into history, but the underlying framework for evaluating the IT business performance impact should not change much over several years. This situation makes it possible to accomplish many of the objectives discussed in Keys 1-9: keeping individual risks in view, reducing costs, increasing gains, accelerating gains, and tactfully keeping your Reference Group and other managers aware of their joint responsibilities in delivering IT business benefits.

Your Next Steps

The nine keys above work with most good approaches to business case building. They are especially applicable, however, with the business case structure and content presented in Business Case Essentials (www.business-case-analysis.com/business-case-essentials.html).

Solution Matrix Ltd® 292 Newbury St Boston MA 02115 USA

Phone +1.617.849.8478 • Contact Form • Privacy Policy • About Us • Sitemap

Terms of Service • Refunds • Customer Service • Safety & Security

Copyright © 2004–2024 by Solution Matrix Ltd • All Rights Reserved