What Is a Sinking Fund?

The name for these funds means "retiring the debt" or, more colorfully, "sinking the debt."

Businesses use the sinking fund concept to build a pool of cash, which they expect to use for paying off a specific debt or covering another specific contingency.

Define Sinking Fund

A sinking fund is essentially a special-purpose savings account. Business organizations create sinking funds solely to ensure they have funds on hand by a specific date, to cover specific spending needs.

Businesses normally build sinking fund deposits into their periodic budgets.

The sinking fund concept appears in personal finance, as well, when individuals periodically set aside funds for a specific future use, such as purchasing holiday gifts, a vacation trip, or upgrading a home.

The difference between personal sinking funds and sinking funds in business, however, is that the business is legally bound to use these funds only for the stated purpose, while individual savers are legally free to use their accumulating funds, ultimately, for any other purpose.

Explaining Sinking Funds in Context

Sections below further explain sinking fund principles, demonstrate sinking fund First, calculations, and illustrate basic accounting transactions, emphasizing four themes.

- First, defining "Sinking Fund" and similar terms, including the reason for the name "Sinking Fund."

- Second, differences between the Sinking Fund and ordinary savings accounts of contingency funds.

- Third, financial reporting of sinking fund transactions.

- Fourth, example calculations showing how to calculate sinking fund payments that achieve a target sum.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Why Are These Funds Called Sinking Funds?

The name Sinking Fund refers to "retiring the debt" or, more colorfully, "sinking the debt." Sinking fund is apparently the English version of fondo d'ammortamento, a term in use on the Italian Peninsula from the 15th century onwards, referring to a funding pool existing specifically to retire public debt. By the 18th century, the term was in use in Great Britain for funds created for the purpose of reducing national debt. By the middle of the 19th Century, the term was in common use in the United States, referring primarily to funding pools for the purpose of retiring corporate and public debt from bond issues.

In the 21st Century, business firms and government organizations in the United Kingdom use sinking funds primarily to set aside cash specifically for acquiring or replacing capital assets. In North America, by contrast, the primary business use of the term involves funds set aside specifically for retiring bonds or stock share debentures.

The law in some localities requires owners and debtors to establish and build sinking funds to specific target levels, calling these funds maintenance funds or even emergency funds. Sinking funds of this kind, when subject to country-level legislation may also carry the name Multi-Unit Development (MUD). So-called Multi-Unit Development Acts in various countries stipulate penalties for anyone using MUD funds for anything other than their original purpose.

Sinking Funds vs. Savings Accounts

Emergency Fund vs. Contingency Fund

In principle, there are only two differences between a sinking fund and an ordinary savings account:

- First, fund owners may use sinking fund money, ultimately, only for the purpose they designate when creating the fund., during fund life, fund owners "raid" the fund and spend for anything else, the fund fails its purpose, and the "raiders" may face legal liability.

With ordinary savings accounts, however, account owners may spend for various purposes, some of which may even be unknown when they create the account. - Second, ordinary savings accounts usually do not have a specific end of life or target maximum balance in view.

With sinking funds, account holders set the periodic payment amounts so as to bring fund accumulation to a specific target value by the end of the fund's life.

Locally applicable GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) in most cases permit spending from sinking funds only under the following condition: Corporate directors or officers certify that fund's sole purpose is to meet a known future spending need of a non-recurring nature.

Emergency Fund vs. Contingency Fund

Organizations also create other varieties of savings accounts known as Emergency Funds or Contingency Funds. These are similar in purpose to sinking funds, except that unlike the sinking fund, the organization may use emergency or contingency funds to cover a range of different emergencies or contingencies, including situations they did not anticipate at the beginning of fund life.

and (2) target balances for these funds are arbitrarily set figures, whereas the sinking fund target balance is known precisely, determined by known needs.

Recording and Tracking Sinking Fund Transactions

Private individuals, of course, may build sinking funds (gift funds, or vacation funds) as cash pools, which they store at home, or in ordinary savings accounts. Business firms sometimes also build small sinking funds as cash pools in an on-site "cash box,," for example, to accumulate funds for a seasonal "Office Party."

However, the larger sinking funds that businesses use for retiring debt, acquiring assets, or making investments, must (1) appear in the firm's accounting system, and (2) earn interest on fund deposits during fund life. This means that the firm's sinking funds involve at least one accounting system account, and one bank savings account.

The sinking fund itself exists as a balance sheet asset account, normally appearing under Long Term Investments. Sinking fund accounts do not belong under Current Assets even though they are normally cash accounts. They are not Current Assets because the firm cannot use them as working capital. These funds must remain on deposit until the end of fund life, when they serve their original purpose.

Business firms deposit payments for a major sinking fund into bank savings accounts, not into an on-site cash box. Important sinking funds build over multi-year lifespans, and therefore must earn interest until their end of life.

Where do Sinking Fund Transactions Impact Accounting System Accounts?

Sinking fund transactions can, in principle, impact all five accounting system account categories.

- The sinking fund itself normally appears as Long Term Assets account, often with the name Reserve Account.

- When the fund exists for the purpose of paying off debt (e.g. debentures, bank loans, or bonds), the debt appears in one or more Liability accounts.

- Regular payments in the sinking fund are typically transfers from an Equity account, such as an account for "undivided surplus profits." The firm may also pay into the account by transferring cash from another Assets account, such as Cash on Hand.

- Earnings from sinking fund deposits can enter the accounting system as Revenue account transactions.

- Sinking fund losses may enter the accounting system as Expense Account Transactions.

Sinking Fund Calculations Are Annuity Calculations

The final step in setting up a sinking fund is calculating the exact amount to pay into the fund in regular period payments. Fund owners calculate the exact payment amount that will accumulate over the fund lifepan to meet the spending need.

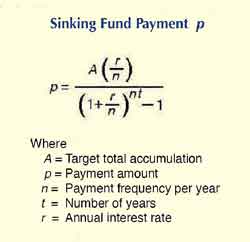

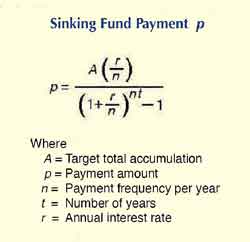

This amount is p in the sinking fund payment formula.

Input Data for Calculating Sinking Fund Payments

When a business firm sets up a sinking fund, the firm already knows the purpose of the fund, that is, for paying off a known liability, acquiring a specific capital asset, or making a specific investment. Calculating the payment value, p, then uses four additional data items as input:

- First, the fund life span.

This is the number of years over which payments will be made into the fund, appearing as t in the payment formula. - Second, the target accumulation.

This is the amount the fund must accumulate to meet its purpose.

This amount is A in the payment formula. - Third, payment frequency.

This is the number of payments per year, appearing as n in the formula. - Fourth, the annual interest rate.

This normally the rate the bank pays for funds on deposit. Payments into the fund will earn compound interest at this rate throughout fund life. This rate is r in the payment formula.

Note, however, bank interest rates fluctuate over time. For this reason, firms often take a conservative approach, using a rate for the calculation representing the lowest likely rate over the fund lifespan rather, than the current bank rate. This helps ensure that sinking fund accumulation will be adequate, even if interest rates fall below the current level.

These four data points are sufficient input for calculating sinking fund payment p.

The formulas in this section, incidentally, are well-known as annuity calculations. The annuity view is appropriate because the sinking fund is mathematically equivalent to an annuitant, receiving periodic payments from an annuity.

Example Calculation: Sinking Fund Payment

Consider a firm setting up a 20-year sinking fund that must reach $1,000,000 in value after 10 years. Assume that the fund resides in a bank account paying 5% annual interest. If the firm anticipates making quarterly payments into the fund (payments 4 times a year), how much must it pay for each payment?

The formula will yield payment p using these data:

- A= $1,000,000

- t = 10 years

- n = 4 payments per year

- r = 5% annual interest rate

The payment formula using these data in Microsoft Excel notation is:

- p =(1000000)*(((0.05/4))/(((1+(0.05/4))^(4*10))-1))

- p = $19,421.41

In other words, forty quarterly payments of $19,421 into the sinking fund will accumulate $1,000,000. The firm must now plan on budgeting quarterly payments of this amount across the sinking fund life.

Reverse Calculation: Sinking Fund Future Value as a function of Payment

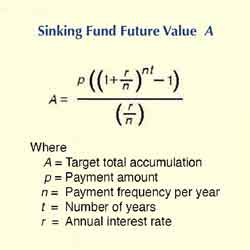

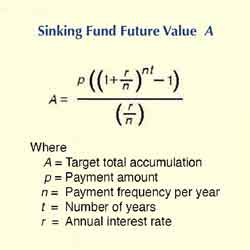

Sinking fund owners may want to perform the reverse calculation, that is, start with a known payment amount and from that calculate the total accumulated future amount (Future Value, FV).

In that case, they solve the payment calculation formula above for amount A, as the example shows.

This example uses the same payment frequency n, number of years t, and annual interest rate r, as the above example. To show how the FV formula serves as a check on the payment value results, the example uses as payment amount p the previous result example above,

p = $19,421.41390858

Note that multi-year interest results, using exponential calculations as in this example, require high precision input. Without precision input, results are likely to include significant rounding error. Payment amount p for the FV calculation, for instance, is precise to eight decimal places.

The future value FV formula (accumulation A formula) using these data in Microsoft Excel notation is:

A = $19421.41390858*(((1+0.0125)^40)-1)/0.0125

A = $1,000,000

The FV calculation therefore confirms the earlier payment result of $19,421, showing that 40 quarterly payments of this amount do lead to a sinking fund accumulation of $1,000,000 after 10 years.

A firm might also use the FV formula to find exactly the target accumulation amount it can achieve, given a known maximum payment amount it can afford.