Business Case Analysis: What's the Purpose?

Decision-makers turn to business case analysis for objectivity, transparency, and the confidence they need to choose the best business decision.

Businesspeople everywhere are losing patience with management error, while demanding more accountability for decisions and plans. And, everywhere, the competition for scarce funds is increasing.

No surprise then, that many organizations now require business case support for project, product, investment, and capital acquisition proposals.

Define Your Terms! What's a Business Case?"

Even though everyone talks about the business case, surprisingly few really know what that means. Few have a grasp on the full business case definition:

Define Business Case

The Business Case is an analysis that delivers two kinds of information about the consequences of an action or decision:

- Forecasts. The business case asks "What happens if we take this or that action?" Case results answer in business terms: business costs, business benefits, business risks.

- Proof. Reasoning and evidence make the case for choosing one action over another. The case proves in compelling terms why the chosen action is the better business decision.

Businesspeople sometimes call BCA by other names, probably to highlight the particular focus of a study. They may call the business case …

Financial Justification

Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA)

Total Cost of Ownership Analysis (TCO)

Return on Investment Analysis (ROI)

In any case, what they mean with these terms usually fits the two-part BCA definition above.

Decision makers and planners rely on solid business case analysis to build the understanding and confidence they need to take action. They need credible forecasts, but they also need trustworthy proof they are choosing the best course of action.

Five Reasons to Write a Business Case.

Businesspeople turn to business case analysis to meet several different information needs.

- Financial Justification.

The justification business case determines whether or not the proposed action meets any one of three criteria. The action may be justified if it meets one or more of these criteria:- Earns enough to cover its costs. It pays for itself.

- Is more profitable than other available options or, it simply promises a return on investment that is acceptable. Organizations sometimes define target return metrics in terms of Simple ROI, IRR, Payback Period, or NPV.

- Is the least costly solution available. Or, more simply, the cost of the action is acceptable.

- The analyst designates at least one of these as the meaning of justification for a given proposal.

- Decision Support

Given two or more possible courses of action, the business case provides objective, quantitative measures for deciding which action is the better business decision. The case also shows whether or not business risks with possible actions are acceptable.

Capital review committees, for instance, often require business case support for incoming spending proposals, to help prioritize and choose among competing funding requests. - Business Planning.

The business case can deliver accurate forecasts of future spending needs and incoming revenues. - Management and Control.

For project and program managers, the case reveals critical success factors and contingencies they must manage to target levels. For business investments of all kinds, the business case provides practical guidance for minimizing costs, maximizing returns, and mitigating risk. - Accountability.

A solid case shows directors, regulators, and government authorities that decisions were made responsibly, with sound judgment, conforming to laws and policies.

The case builder may start with one of these roles in mind, several roles, or all five.

Who Builds the Business Case?

Businesspeople are finding that business case is not just a job for Finance in the back office. Financial experience helps in the case-building process, of course, but the most useful BCA knowledge lies elsewhere. Those best prepared to build the case are those who

- Know the details of day-to-day operations in the business unit.

- Understand the drivers for employee and group performance.

- Have a successful track record managing projects and programs.

As a result, case-building responsibility today rests squarely on those who propose and those who take action. Product managers, engineers, consultants, project managers, IT directors, strategists, business development managers, line managers, and others "in the trenches," know that meeting business case needs means building the case themselves.

Success Begins in the Eye of the Beholder

Not everyone understands the meaning of business case success alike. To the manager seeking project funding, funding approval might seem like a success. To the salesperson, a BCA that helps close a sale seems like success. Granted, any decision in the case builder's favor feels like success. Nevertheless, case builders better serve their interests—and their organization's interests—by defining business case success in terms of these three criteria.

- Credibility.

The case is credible if stakeholders and decision-makers believe the case rationale and case predictions. - Practical value.

- The case gives decision-makers and planners confidence to act.

- It enables them to manage the action for optimum results.

- It discriminates clearly between proposals to implement and those to reject.

- Accuracy.

The case predicts accurately what happens.

Build, and Deliver the Winning Business Case

Sections below focus on two themes

- First, the origins, definition, and standardization of the business case concept.

The modern business case evolved from a nineteenth-century concept, benefit-cost analysis for government public works projects. The twenty-first-century version of the concept still lacks universal standards. There is an emerging consistency, however, in the local business case standards now turning up in government and private industry. - Second, a step-by-step guide to writing a successful business case.

The 6D Business Case Framework appearing here has proven uniquely successful achieving case results that meet the two-part business case definition (above), while meeting business needs for decision support, planning, management and control, and accountability reporting.

Contents and Resources

Birth of the Business Case Concept

Govt Cost-Benefit Becomes Modern Business Case

Origins: Economics, Engineering, Government Works

Evolution of the modern business case began in nineteenth-century Paris, when the government tackled a special public policy problem: finding the optimum toll for using a toll bridge.

The solution came from Jules Dupuit (1804–1866), Chief Engineer for the City of Paris and later Inspector-general of the Corps des Pont et Chaussees. Dupuit was by training a civil engineer, but also a talented self-taught economist. The modern business case has roots in his 1844 Paper, On Tolls and Transport Charges.1 Re-published and elaborated in 1894, this work sets up several issues that are rightly seen as foundation concepts for the twenty-first-century business case:

- How to identify, measure, and value benefits.

In Dupuit's terms, this value is relative utility. His term for this kind of study was benefit-cost analysis. - The efficiency and distribution of benefits.

- The definition of consumer surplus.

This is the difference between the total amount consumers would willingly pay for a good or service, and the market price they actually pay. - Consumer demand and price discrimination

Dupuit focused on government public works and he wrote extensively on the government role in railways, bridges, and road systems. The focus on public works spawned a legacy mandate that is alive and well today for government organizations everywhere:

The government business case measures benefits in terms of "value delivered" to a given population.3

What Is the Business Case Role in Business Today?

Business case applications today have moved well beyond the classical focus on government public works. Companies, governments, and non-profits alike, either recommend or require business case support in quite a few formal process areas:

- Board of Directors governance.

- Planning strategy.

- Targeting strategic objectives.

- Managing projects.

- Managing & evaluating programs.

- Product management.

- Planning & evaluating business models.

- Business model planning.

- Choosing & managing investments.

- Prioritizing capital acquisitions.

- Managing asset life cycle.

- Choosing & evaluating pricing models.

- Reporting environmental compliance.

- Budgeting and funding approval.

- Forecasting revenue and costs.

- Selecting vendors, vendor services, products.

- Delivering sales proposals.

- Establishing and reporting accountability.

- Negotiating partnerships and alliances.

- Negotiating labor contracts.

Notice especially that business case requirements do not by themselves add value to a process. Business case requirements are worthwhile and enforceable only where there are business case standards. Standards are indispensable wherever organizations require the BCA.

Where Are the Business Case Standards?

Business Case Analysis often appears under other names. The writer may call it Financial Justification, Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA), Total Cost of Ownership Analysis (TCO), or Return on Investment Analysis (ROI). What people mean with any of these terms usually agrees with the twofold Business Case definition above.

Everyone should know, however, that none of these terms—including business case—has widely-agreed standards. Consequently, organizations must write their own rules for case content and the case-building process. Remember, however, that cases written elsewhere, under other local standards, can be very different.

Standards are necessary wherever business case requirements are in force. The reason is that case builders and decision-makers must ultimately agree that cases either are or are not acceptable. Reaching agreement is difficult or impossible, absent standards that are clear, objective, and testable.

Dupuit's 1844 benefit-cost analysis had specific methods and criteria for evaluating the legitimacy of a given benefit-cost study. With just a few exceptions, the same is not true for most business case systems available today. Two exceptions are the British Government's Better Business Case, and the Solution Matrix 6D Business Case Framework (appearing below). Versions of both systems serve successfully as local business case standards for:

- Government organizations: The US Department of Defense, the UK National Health Service, The US Postal Service, California Sonoma County, Washington State Government (USA), NASA (USA), the Danish Ministry of Finance, and the Ghana National Communications Authority, and many others.

- Multinational corporations: Ericsson, IBM, Airbus, Allianz Group, Cisco Systems, and Petronas, and many others.

- Educational and Non-profit organizations: Baylor University (US), University of Pennsylvania (US), University of Otago (NZ), Sprott School of Business (CA), CARE, and many others.

How to Write the Winning Business Case

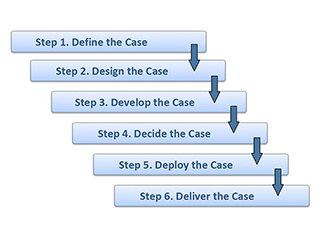

Six Steps to Compelling Results

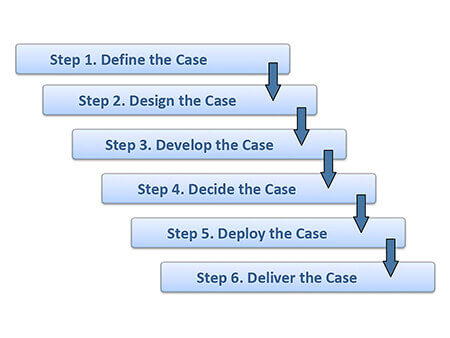

Six sections below guide you through the steps of the Solution Matrix 6D case-building process. For each step, the case builder's task is to complete several business case "building blocks." Think of the completed business case as a wall, or structure, built from these blocks. The structure either stands or falls, depending on the builder's skill in arranging blocks so that they support each other.

Steps and Building Blocks Have a Natural Order

The next sections present case-building steps and building blocks in a particular order. Notice especially that the prescribed step sequence is vital, but the ordering of blocks within each step is also crucial.

- Step order is vital for building a seamless, logically sound rationale. The rationale makes the case: "These results follow from this action!"

- Order is crucial because later blocks depend on earlier blocks. The cost model, for instance, requires already-completed subject, purpose, and scope statements.

Design, Build, Deliver the 6D Business Case

Step 1 Define the Business Case

The case builder defines the case before taking any other steps. This step begins by taking inventory—or summarizing—the information needs of primary stakeholders and managers who have an interest in the case. Usually this means identifying first the business objectives they expect the subject of the case to address. These objectives might include, for instance, reducing costs, improving employee productivity, or increasing sales revenues.

Case definition continues when the case builder proposes specific actions to address these objectives. The case may consider acts such as funding a project, making a capital acquisition, launching a product or service, or making a financial investment. The proposed action becomes the business case subject.

Describing all available courses of action when case building starts, helps identify the different business case scenarios the case will examine.

Case definition is complete when the case builder and stakeholders describe the purpose of the case. Before designing the case (Step 2), the case builder must first answer "purpose" questions like these: Why is the case being built? Who will use it? For what purpose? What information do they need to meet that purpose?

Step 1 Directions for Defining the Case

- Write the subject statement.

- Describe proposed actions and scenarios to analyze.

- Also, Identify the business objectives the case addresses.

- Describe proposed actions and scenarios to analyze.

- Write the purpose statement.

- Explain who will use the case and for what purpose.

- Also, describe information the case must deliver to meet the purpose.

- Explain why these objectives are important to the organization.

- Also, show how these objectives align with business strategy.

- Also, explain how current strengths, threats, constraints, and opportunities that impact action choice.

Design, Build, Deliver the 6D Business Case

Step 2. Design the Business Case

Clear descriptions of key assumptions and methods help the case builder ensure that all scenarios build by the same rules. As a result, case builder and stakeholders know that different scenario results are comparable.

Clear and complete design statements are necessary, so that stakeholders and others who rely on business case results can see for themselves where business case results come from.

Step 2 (Design) creates the "architectural blueprint" for a structure that makes this transparency possible. Design information here serves as the necessary Methods Section of the business case report.

Step 2 Directions for Designing the Case

- Designate case scope and boundaries.

- Explain whose costs and whose benefits belong in the case.

- Also, stipulate the analysis period in view (starting date and duration).

- Identify assumptions essential for forecasting costs and benefits.

- Develop reasoning to legitimize outcomes as benefits.

- Show how specific outcomes contribute to meeting business objectives.

- Explain metrics that make nonfinancial outcomes tangible.

- Explain how the analysis assigns values to nonfinancial outcomes.

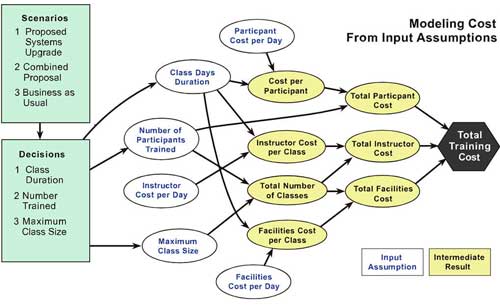

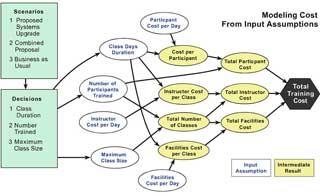

- To make scenarios comparable, present a single cost model that covers all scenarios.

- Identify all relevant cost categories for the case.

- Identify individual cost items for each cost category.

- Explain methods for estimating costs

Design, Build, Deliver the 6D Business Case

Step 3. Develop the Business Case

In Step 3, the case builder forecasts cash inflows and outflows for each case scenario. The result is a cash flow statement for each. In this step, the case builder presents summaries and analyses objectively and directly, keeping interpretations and explanatory text to a minimum.

The Step 3 cash flow results are data for further analysis and interpretation in steps 4, 5 and 6.

Step 3 Directions for Developing the Case

- Forecast each scenario's likely costs and benefits as cash flow events.

- Also, forecast impacts on nonfinancial key performance indicators (KPIs).

- Summarize each scenario's cash inflow, cash outflow, metrics results, in a scenario-specific cash flow statement.

- Also prepare an incremental cash flow statement for each scenario. Incremental cash flow is the difference between Expected cash flow in a full-value cash flow statement and expected cash flow in a baseline scenario ("business as usual" scenario).

Design, Build, Deliver the 6D Business Case

Step 4. Decide the Business Case

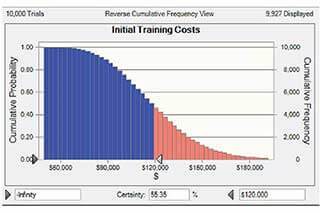

In business—as in gambling—the wise investor or wise bettor knows that choosing an action option requires more than a knowledge of projected returns, or ROI. Those figures show only what happens if returns appear as investor hopes.

The wise choice, however, is based on a comparison of (1) potential returns with (2) the likelihood (probability) that they appear.

Step 4 Directions for Deciding the Case

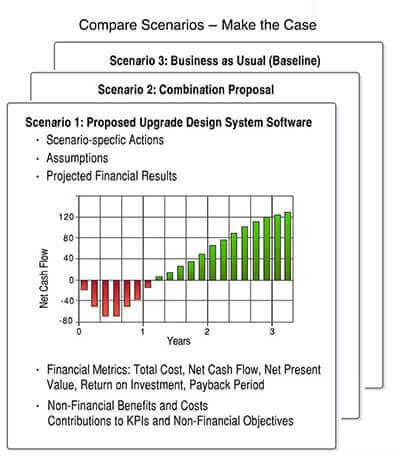

- Analyze and compare financial metrics from each scenario.

- Compare impacts on Important KPIs and other tangible nonfinancial measures.

- Show how underlying assumptions impact business results.

- Measure the likelihood of different outcomes.

- Identify significant risks.

Design, Build, Deliver the 6D Business Case

Step 5. Deploy the Business Case

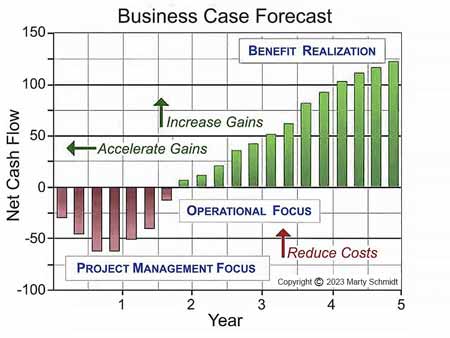

Building blocks in step 5 address the most substantial issues appearing initially in the introductory sections of the business case report. In Steps 3 and 4, the author “lets the numbers speak for themselves.” In Steps 5 and 6, however, the case writer interprets the numbers and connects them to objectives, decisions, and actions.

Step 5 Directions for Deploying the Case

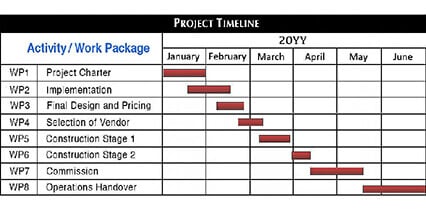

- Recommend one scenario for action, referring to likely (1) incremental financial results, (2) impacts on important nonfinancial measures, and (3) risk and sensitivity analysis results.

- Set targets for critical success factors and contingencies to manage.

- Provide tactics for lowering costs, increasing gains, and accelerating gains.

- Identify risks to monitor over time.

- Provide tactics for mitigating risks.

Design, Build, Deliver the 6D Business Case

Step 6. Deliver the Rewards You Promised

In many organizations, the active role of the business case ends with the submission of a case report, a formal case review, or a decision to fund a proposal. That is unfortunate because the business case analysis, when complete, can provide extremely valuable practical guidance to management during the implementation of the proposal or the life of the investment—guidance for maximizing returns, minimizing costs, and minimizing risks.

For that reason, the 6D Business Case Framework does not end with Step 5, Deploy. The framework has an active role through one more stage, Step 6: Deliver the Business Case. This stage is complete only when the initiative or the investment life ends.

Step 6 Directions for Delivering the Case

- Plan and implement the recommended action scenario.

- Monitor stakeholder success in tracking changes in key assumptions and adjusting control actions when necessary. Let the Step 4 risk and sensitivity analyses and Step 5 recommendations guide real-time investment control. show stakeholders how to maximize investment performance: Minimize costs, maximize gains, accelerate gains.

- Validate and update significant assumptions continuously.

- Validate and update the business case financial model continuously as assumptions change and tasks reach completion.

- Validate incoming costs and benefits, continuously, and update business case forecasts when necessary.

Business Case vs. Business Plan

How Are They Different? How Are They Related?

Some people in business use the terms business case and business plan more or less interchangeably. Some use one term when they mean the other. Responsible decision-making and planning, however, call for a precise understanding of each term's meaning and the differences between them.

As a result, prudent business case builders take care to be sure that everyone involved with the case understands these terms precisely.

In fact, the critical distinction between them is clear, simple, and easy to summarize.

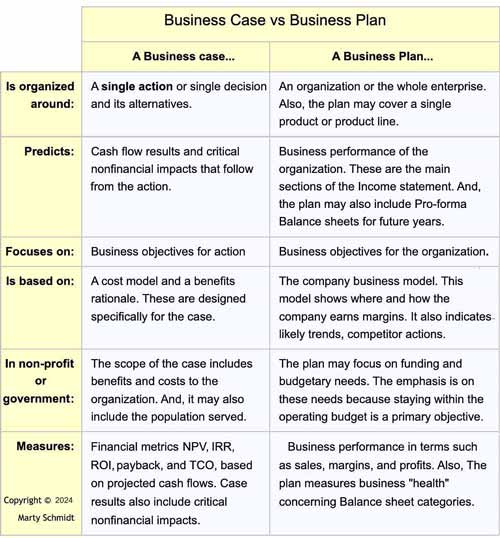

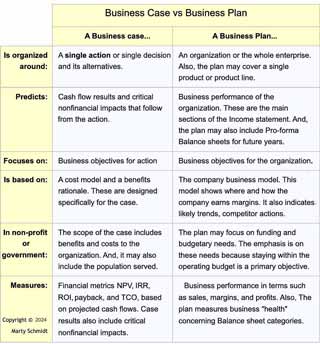

The business case is about an action, while the business plan is about the business.

Questions For the Business Plan

The business plan addresses issues like these:

- What will the business look like in one year? In three years? In other words, what will financial position and earnings look like then?

- How can the business achieve those results?

- What sales, margins, and revenues can we expect next year?

- How long will it take for a start-up company to earn a profit?

The business plan answers such questions by providing:

- Predictions and target objectives for future financial results.

- Important risk factors that would bring different business results. The plan also presents strategies for dealing with threats and reducing risks.

- A business model. The model shows where and how the company expects to spend money, bring in revenues, and earn margins.

- Fundamental assumptions and trends for projecting business results. These may focus on business volume, market demand, and competitor actions. Management tracks these factors carefully and updates them when necessary.

- Guidance for setting and prioritizing business objectives.

- Spending and revenue forecast for budgeting and planning.

Questions for the Business Case

The business case focuses on a single action or decision. The business case addresses issues like these:

- What financial outcomes followif we choose option X?

- Are there significant nonfinancial outcomes we expect under option X?

- What is the capital budget impact if we buy service vehicles instead of leasing them?

- How do we justify the investment in new phone technology? Is there a positive ROI?

The business case addresses such questions by projecting cost and benefit cash flows that follow from the action. Also, the business case also anticipates nonfinancial impacts on crucial key performance indicators.

Comparing the Business Case to the Business Plan

The table below summarizes and contrasts critical differences between the business case and business plan.