Business Case Analysis: What's the Purpose?

Double-Entry systems are costly to implement and require training in accounting to use. Why, then, do most businesses worldwide choose Double-Entry accounting over single entry?

Start-up firms creating their accounting systems must decide whether to manage financial reporting and record-keeping either with a Single-Entry System or a Double-Entry System.

The choice between these two accounting approaches has a profound impact on how the firm bills customers and accepts payments, pays its bills, reports earnings and tax liabilities, and assures government authorities that the firm complies with tax laws and employment regulations. The choice also impacts the firm's ability to track and manage assets, debts, and owner's equity.

Define Single-Entry and Double-Entry Accounting

In Single-Entry Accounting, a single financial event calls for just one account entry.

In Double-Entry Accounting, each financial event (such as cash inflow from a customer sale) calls for at least two accounting system impacts.

- First, a credit entry in one account.

- Second, at the same time, an equal, offsetting debit entry in another.

Most Firms Choose the Double-Entry Approach

The majority of business firms worldwide rely on double-entry systems, even though they are more complex and more difficult to use than the more straightforward alternative, single-entry systems.

Using a double-entry system requires at least some level of formal training in accounting. The user must, for instance, have a solid grasp of concepts such as debit, credit, Chart of accounts, and the two Accounting equations. By contrast, just about anyone who can arrange numbers in a table and add and subtract, can set up and use a single-entry system.

All public companies and almost all large firms nevertheless choose the double-entry approach. They choose double-entry accounting because it is nearly impossible for them to meet government and regulatory requirements for reporting and record-keeping using a single-entry system. And, with a single-entry system alone, large firms cannot accurately track their assets, liabilities, equities, revenues, and expenses.

Double-Entry Accounting Purposes

The practice of using two account entries for every transaction in this way serves two purposes:

Purpose 1. Built-In Error Checking

Firstly, the double-entry system builds-in a form of error-checking. When accountants and bookkeepers apply double-entry methods properly, the sum of all debit entries in the account ledgers for the accounting period must equal the sum of all credit entries. That is, at all times:

Total Debits = Total Credits

A mismatch in these two totals signals that the accounts have a bookkeeping or accounting error. For more on this form of error-checking, see Trial Balance.

Purpose 2. Balance Sheet Balance, Tracking Transactions

Secondly, double entries maintain the balance in the two Accounting equations:

Assets = Liabilities + Owners Equity

Debits = Credits

Maintaining the balance in these equations, in turn, means that the organization's Balance sheet is an accurate basis for assessing the company's financial position, financial structure, capitalization, and financial statement metrics (business ratios).

Double-entry accounting, moreover, uses debits and credits in this way to track five kinds of transactions: Revenues, Expenses, Liabilities, Equities, and Assets. Single-entry accounting, by contrast, recognizes only two types of operations: Cash inflows and cash outflows.

Explaining the Double-Entry System in Context

Sections below further explain Double-entry accounting and bookkeeping, focusing on five themes:

- The rationale and purpose for double-entry approaches in accounting.

- Example transactions illustrating the nature of double-entry accounting.

- Advantages and disadvantages of both single-entry and double-entry systems.

- Reasons that most firms choose double-entry accounting

- The Chart of Accounts as the organizing basis of a double-entry accounting system.

Contents

Medieval Origins, Complex Rules

Why Choose Double-Entry Accounting?

Only Double-Entry Systems Meet All Business Needs

Early forms of double-entry accounting in Europe and Asia date from the late medieval period (1100-1450), as early as the 12th Century. This period saw new activity and new complexities in business, commerce, and banking that were unknown in the several centuries earlier, the "dark ages."

This period saw, for instance, rising levels of international shipping and commerce. Merchants began selling "on credit," forming partnerships and companies, obtaining funding from private banks, and covering business investments with insurance. Such activities brought new kinds of business transactions. These include activities that complex businesses must track and manage, but which are invisible to simpler accounting systems.

The double-entry approach, in other words, was a response to merchants, bankers, and investors, who found simple cash basis accounting inadequate. They needed systems that support better forms of error-checking. They needed, moreover, systems that recognize transactions for acquiring assets, earning revenues, incurring expenses, creating debt, and owning equities.

Luca de Pacioli, "Father of Accounting."

Double-entry-like accounting records from the 14th century survive in Europe and Asia. Credit for writing and publishing the first systematic description of the subject in 1494 belongs to Luca de Pacioli (1445-1517), a fifteenth-century Franciscan friar, best-known for Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalità, the earliest known description of double-entry bookkeeping in print. For this reason, no doubt, many refer to Pacioli as the "Father of Accounting."

Luca de Pacioli, incidentally, is also known for writing De Devina Proportione (1497), an attempt to re-discover the "true" shapes and proportions of the classical Roman alphabet. He was born in the village of Sansepolcro in Tuscany but spent most of his working life in Venice, Milan, and Perugia. His career seems to have been driven by his passions for teaching mathematics and writing—counting Leonardo da Vinci among his pupils.

Pacioli did not invent the methods he wrote about in Summa de Arithmetica, but instead, summarized and published for the first time the practices used by Italian merchants of the Renaissance.

The Meaning of Account in Accounting

Building Blocks of the Accounting System

Every profit-making company in business sets up an accounting system to manage and track of its assets, liabilities, equities, revenues, and expenses. The accounting system also serves as the data source for the financial reports the company must file periodically.

The basic building block in the system is the account, which is the name for a place or holder for recording balances and balance changes (additions and subtractions) for one specific purpose. In fact, "specific purposes" are divided into five categories, and these categories represent the five—the only five—kinds of accounts possible in an accounting system. Note that the five account categories fall into two groups: Firstly, the Balance sheet accounts, and Secondly, the Income statement accounts.

Three Balance Sheet Account Categories

- Asset accounts: Items of value the firm owns and uses for generating earnings in its primary line of business. For example:

"Cash on Hand"

"Accounts Receivable" - Liability accounts: Debts the business owes. For instance:

"Accounts Payable"

"Salaries Payable" - Equity accounts: Owner claims (Shareholder claims) to business assets. For example:

"Owner Capital"

"Retained Earnings"

Two Income Statement Account Categories

- Revenue accounts: Incoming revenues, primarily from the sale of goods and services. For instance:

"Product Sales Revenues"

"Interest Earned Revenues" - Expense accounts: Expenses the firm incurs in the course of business. For example:

"Direct Labor Expenses"

"Advertising Expenses"

Every Transaction Impacts Two Accounts

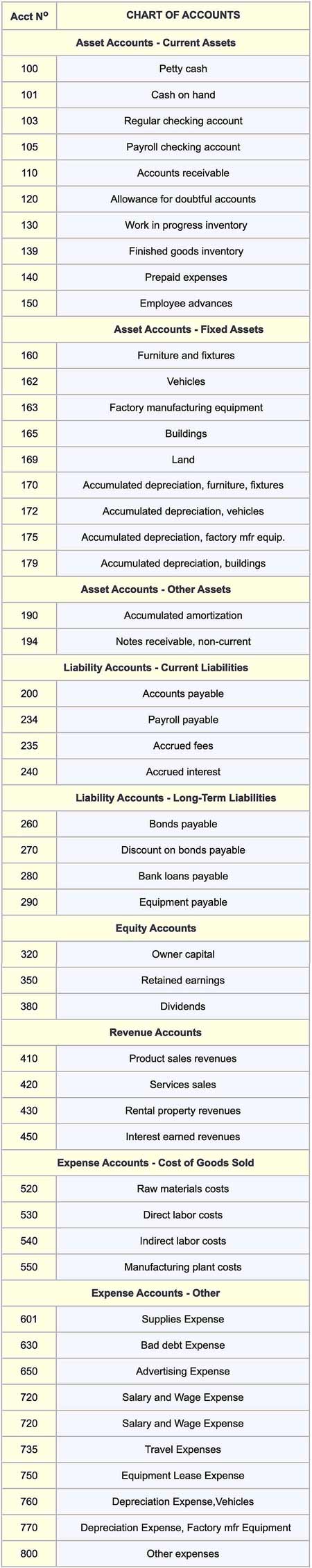

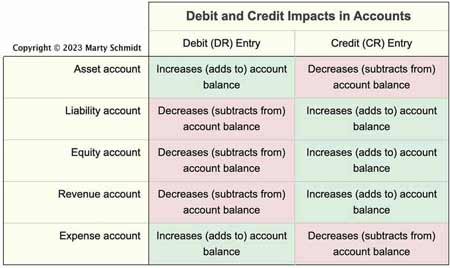

In reality, even a small business may identify a hundred or more such accounts for its accounting system, while a large company may use many thousands. Nevertheless, for bookkeeping and accounting purposes, all named accounts fall into one of the five categories above.).

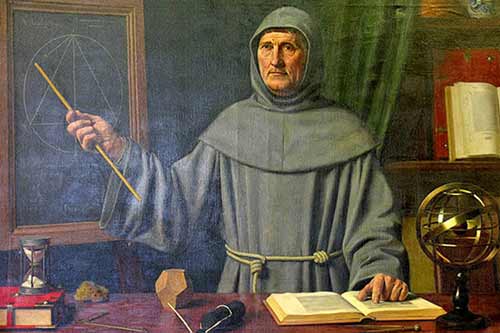

For firms that use double-entry systems, every financial transaction causes two equal, and offsetting account changes. The change in one account is a debit (DR), and the change in another is a credit (CR).

Debits and Credits Impact Account Categories Differently

How the bookkeeper and accountant handle each transaction for an account depends on which of the five account categories includes the account. Also, whether a debit or a credit increases or decreases the account balance also depends on the account's category. Exhibit 1 summarizes debit and credit conventions for the five account types.

Suppose, for example, that a company buys an asset with a value of $100,000.

The firm will register an increase (debit) of $100,000 to an asset account. This account could be, for instance, Account 163 from the Chart of Accounts below, Factory Manufacturing Equipment. A debit transaction increases the balance of this account because this is an asset account. Now, however, the Balance sheet is temporarily out of balance until the firm makes an offsetting credit of $100,000 elsewhere in the accounting system:

- The firm could, for instance, credit $100,000 to another asset account, reducing that account balance by $100,000. That account could be asset Account 101, Cash on hand.

- If instead, the firm finances the purchase with a bank loan, instead of the company's cash, the offsetting $100,000 transaction could be a credit to a liability account. That could be Account 171, Bank Loans Payable. A credit to a liability account increases the account balance.

Keeping the Balance Sheet Balance

In this way, the basic accounting equation always holds. Firstly, the Balance sheet always balances:

Assets = Liabilities + Equities

Secondly, for every pair of account entries that follow from a single transaction:

Debits = Credits

Contra Accounts / Valuation Allowance Accounts

Contra Accounts Reverse the Debit Credit Rules

Not all accounts work additively with each other on the primary financial accounting reports—especially on the Income statement and Balance sheet. There are instances where one "account" works to offset the impact of another account in the same category. The so-called contra accounts "work against" other accounts in this way. In some situations, the contra accounts reverse the debit and credit rules from the table above.

Contra asset and contra liability accounts are also called valuation allowance accounts, because they work to adjust the book value, or carrying value for assets or liabilities, as the examples below show.

Balance Sheet Contra Assets Example

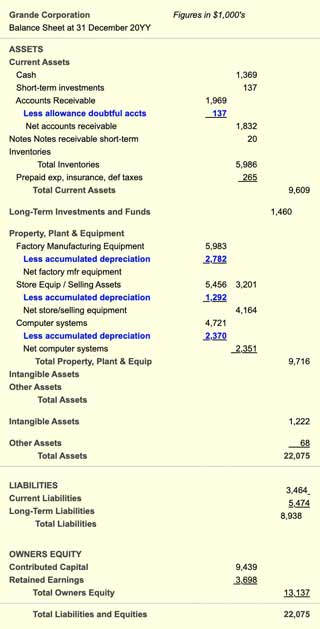

The Balance sheet examples running throughout the Business Encyclopedia have several contra account examples. Exhibit 2 below is a balance sheet extract highlighting four contra asset account entries:.

From the example Chart of Accounts below, you can see that Accounts Receivable (Account 110) and Allowance for doubtful accounts (Account 120) are both asset accounts. Allowance for doubtful accounts, however, is a contra-asset account that reduces the impact (carrying value) contributed by Accounts receivable. The Balance sheet result is a "Net accounts receivable" less than the initial Accounts receivable value.

In the same way, Account 163, Factory Manufacturing equipment carries the value of these assets at historical cost—the actual cost of acquiring these assets. This value will not decrease as long as the company owns the assets. However, the asset's book value does change downward from year to year, as the balance sheet shows. Contra Account 175, Accumulated depreciation, factory manufacturing equipment, is taken from the Account 163 value, to produce the Balance sheet result Net factory manufacturing equipment.

Contra Asset Impacts on Income Statement Accounts

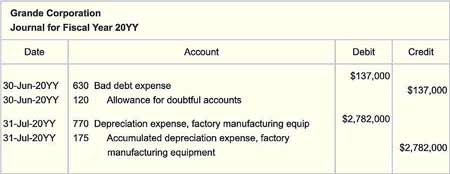

In each case above, incidentally, there is also involves an expense category account. These expense accounts appear on the Income statement, not the Balance sheet. In the first example, the expense account is "Bad debt expense" while in the second case, the account is "Depreciation expense for factory machinery."

The offsetting debit and credit transactions might look appear as follows in the bookkeeper's journal.

All four transactions add to the value (balance) of the accounts they impact. Debiting each of the two expense accounts adds to account value, as the table in the previous section indicates. However notice here that crediting the two asset accounts adds to their value as well—just the opposite of what the same table prescribes for ordinary asset accounts. For contra accounts in this situation, the rules reverse so that the first equation Debits = Credits still holds for every pair of transactions. The examples also show why a contra asset account is said to hold a credit balance.

Contra Liability and Contra Expense Accounts

The above examples show contra asset accounts, but there are also examples of contra liability accounts and contra expense accounts that operate in the same way. For instance, on the liabilities side of the Balance sheet, a long-term liability account Bonds payable may be accompanied by another liability account, a contra liability account called Discounts on bonds payable. The value in the contra account reduces the company's actual liability from the stated figure in "Bonds payable."

Contra liability accounts and contra expense accounts—like their contra asset counterparts—also reverse the debit/credit "rules" from the table in the previous section. An addition to a liability account, for instance, is usually a credit, but to a contra liability account, the increase is a debit. For this reason, the balance in a contra liability account is a debit balance.

Chart of Accounts

Full Scope of the Double-Entry System

The example chart of accounts below is merely an extract from a more realistic "Chart of accounts," and not a complete chart. This example shows the structure and general approach to account numbering and naming, but a real example—even for a small company—would list many more accounts.