What is the Matching Concept in Accounting?

The accrual accounting matching concept helps ensure accuracy in earnings reports.

Define Matching Concept

In accrual accounting, the matching concept is the idea that taxpayers reporting their income and expenses recognize revenues earned along with the incurred expenses that brought them in the same accounting period.

Note that applying the matching concept requires accrual accounting, by which companies recognize revenues when they earn them and expenses in the period they incur them. Actual cash flows from these transactions may occur at other times, even in different periods.

The purpose of the matching concept is to avoid misstating earnings for a period. Reporting revenues for a period without stating all the expenses that brought them could result in overstated profits.

Explaining the Matching Concept in Context

Sections below further define and illustrate the matching concept. Note especially that the term appears in context with related terms and concepts, focusing on three themes:

- First, how the matching concept in accrual accounting helps ensure that profit reporting is accurate, and that the balance sheet always balances.

- Second, why the matching concept does not apply in cash basis accounting.

- Third, how the matching concept also helps ensure validity for financial metrics such as Return on Investment (ROI).

Contents

Who Defines the Matching Concept?

Who Enforces the Concept?

In the US, Canada, the UK, and in many other countries, accounting principles such as the matching concept appear in GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles). They are also by the organizations behind GAAP. In the United State, this is the Financial Accounting Standards Board, FASB.

Besides the matching concept, two other universally recognized accounting concepts include:

- The materiality concept.

This idea is the financial reporting principle that companies disregard matters are and disclose all essential data. - The historical cost convention

This convention is the practice by which record prices as the price prevailing at the time of the transaction.

Who enforces matching and other accounting principles? A first answer is that enforcement usually falls to the same parties that "enforce" GAAP: Independent third-party auditors.

When an auditor reviews a firm's financial statements, the best possible outcome is an auditor's opinion of Unqualified. This opinion affirms the auditor's judgment that reports are accurate and conform to GAAP. And, this means the auditor finds no issues with matching, materiality, "historical costs," or any other GAAP-defined accounting principle. And, this outcome means the auditor finds no problems with matching, materiality, historical costs, or any other GAAP-defined accounting principle.

Define Your Terms!

Revenue, Expense, Cost, Cash Flow

Accrual Accounting

The matching concept represents the primary difference between accrual accounting and the alternative approach, cash basis accounting. The matching idea, in fact, has meaning only under accrual accounting. The concept refers specifically to matching earned revenues with the incurred expenses that brought them. Matched "revenues" and "expenses" work together in the Income statement equation to determine the firm's net profit for the period

Net Profit = Revenues Earned – Expenses Incurred

While the matching concept is concerned only with revenues and expenses, businesspeople also use quite a few other related terms that are easily confused with "revenues" and "expenses:" costs, cash inflows, and cash outflows, for instance. It is essential, therefore, to understand precisely the meaning of "earning revenues" and "incurring expenses".

Accrual Accounting: Earning Revenues

Under accrual accounting, firms claim revenues when they earn them. Earning "revenues" means meeting two conditions.

- Firstly, revenues must be realizable. Revenues from sales of goods and services are said to be realizable only when there is a good reason to believe payment is forthcoming.

- Secondly, the seller has in fact delivered the goods and services.

Revenues earned during the period, therefore, may exist as accounts receivable, other receivables, or as cash received.

Accrual Accounting: Incurring Expenses.

Under accrual accounting, consuming resources incurs expenses. Note especially that the accountant's definition of "expense" refers to assets.

Expense: A decrease in owner’s equity due to using up assets.

- An expense for delivery vehicle fuel, for instance, uses up cash assets.

- The firm may purchase capital assets, such as a fleet of delivery vehicles, Depreciation expense, over time decreases the book value of these assets.

- For most other kinds of spending, however, firms incur expenses only as they consume resources.

- Firms incur expenses for employee labor, for instance, after employees perform the work. Only then do they, in fact, owe wages or salaries to employees.

- Firms incur floorspace rental expense, over time, only as they occupy the space. For instance, a firm may sign a one-year rental contract for floor space. The agreement, moreover, may call for monthly rent payments due on the first day of each month.

On the first day of the first month, after making the monthly advance payment, the firm does not yet incur an expense. At that point, the firm has instead an asset known as a Prepaid expense. For the accountant, rental "expense" itself builds day by day, as the firm occupies the space. At the end of the month, the Prepaid expense asset has reached zero value, and the monthly rental expense is fully "incurred."

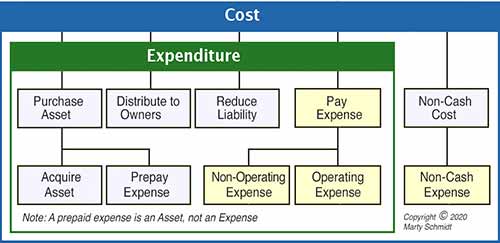

Exhibit 1, below shows the relationships between the terms cost, expenditure, and expense.

Exhibit 1. Relationships among cost-related terms, including Expenditure, Expense, and Cost. These terms have different meanings.

Accrual Accounting

Using the Matching Concept

How does the accountant know which expenses brought which revenues? The answer is that all of the reporting period's "revenue" earnings match only with all "expenses" incurred in the same period.

Consider a firm that sells merchandise from rented shop space. Suppose the firm reports sales revenues for the quarter at $600,000. However, the firm's customers may not, in fact, pay all they owe during the quarter. Some payments may arrive days or weeks the period ends. Also suppose that the firm pays $30,000 for floorspace rent each month, for using the shop, and payment is due in advance on the first of each month.

One day after the quarter ends:

- The firm reports earning $600,000 in revenues for the quarter just finished, even though some of this is still "payable."

- The matching concept requires that the firm report floorspace rental expenses incurred for occupancy during the quarter. The firm will report $90,000 incurred for the quarter just over. It will state this amount even if it has already made the advance payment for the next month.

Cash Basis Accounting:

The Matching Concept Does Not Apply

Under cash basis accounting, firms claim revenues when they, in fact, receive the cash payment for them. Similarly, under cash basis accounting, they report expenses when, in fact, they pay them, in cash. As a result, the matching concept does not apply under "cash basis accounting."

Matching Concept Role in ROI and Other Metrics?

One form of the matching concept helps give meaning to financial metrics at the heart of business case analysis and investment analysis. These analyses ask, mainly, "What happens if we take this or that action? And, they answer in business terms: Business costs, business benefits, and business risks.

These analyses produce financial metrics for evaluating potential action, such as the following metrics:

- Payback period.

- Net present value NPV

- The Internal rate of return IRR

- Return on investment ROI

Investment Metrics have Meaning Only When

Returns Match Costs That Brought Them

In all four cases, the comparison—the resulting financial measures—has meaning only when the outflows bring the inflows under analysis. These metrics, in other words, have a clear message only when analysts compare investment returns to the investment costs that deliver them.

Firms launch projects, initiatives, programs, and products—all with specific objectives in mind. The aim may be, for instance, to improve sales revenues, market share, employee productivity, product quality, or customer satisfaction, for example. The problem for the analyst, however, is that firms typically approach such objectives through multiple actions.

For analysts to claim validity for the ROI metric, they must be able to argue that the returns in view are matched appropriately with (and only with) the costs that brought them. In a complex business environment, prudent decision-makers will question that claim before trusting the ROI.

For examples showing the use of ROI and other financial metrics in business case analysis, to reflect only the costs and benefits directly resulting from an action, see the encyclopedia entries for: