What is an Account?

Accounts are the fundamental building blocks of the organization's accounting system.

In business, commerce, and financial services, the term account has at least two different meanings: Account has one meaning in financial accounting, and a related but different meaning business commerce.

Accounts in Accounting

Define Account (for Accounting)

Accounts are the fundamental building blocks of an accounting system.

- An individual account is an electronic or paper record stating a financial balance for a specific item, class of items, or purpose.

- Each account has a unique account number and account name.

Each new business starts building its accounting system by creating a Chart of Accounts. The chart serves thereafter as the complete and definitive list of active accounts in the system. Depending on the size and complexity of the business, the chart may include dozens, hundreds, or thousands of individual accounts.

Most firms practice double-entry accrual accounting, and for these businesses, the chart of accounts names individual accounts in five categories:

Balance Sheet Accounts

- Assets Accounts

- Liabilities Accounts

- Owners Equities Accounts

Income Statementt Accounts

- Revenue Accounts

- Expense Accounts

Responsibility for updating and reporting balances and transactions in these accounts falls to the firm's accountants, who serve literally as "keepers of the accounts." Sections below further define account categories and illustrate typical transactions for each account type.`

Accounts in Commerce and Financial Services

Define Account (for Commerce, Financial Services)

Account refers to a formal business relationship between two parties, usually a seller and a customer. When one is an account of the other, each party has particular rights, privileges, and obligations.

Firms that sell to other businesses designate their major repeat customers as accounts. In such cases, the seller may appoint one of its own sales staff as Account Manager, focusing primarily on that account. Account managers in this sense are responsible for sales performance with this customer. And, they are also responsible for building a continuing customer-seller relationship with the account.

In a slightly different sense, customers create an account with a seller or service provider. Accounts of this type may have internet access to their accounts, they may charge purchases to their account, and in some cases, the account may carry a financial balance.

In some cases, the seller may carry customers as accounting systems accounts Banks, for instance, refer to depositor customers as Liability accounts. And, banks carry loan customers as asset accounts.

Explaining Account, Contra Account, Chart of Accounts

Sections below further define and illustrate the term account in in the accounting context , along with similar concepts, emphasizing four themes:

- First, definition of account, and how accounts in the Chart of Accounts are the organizing basis of an accounting system.

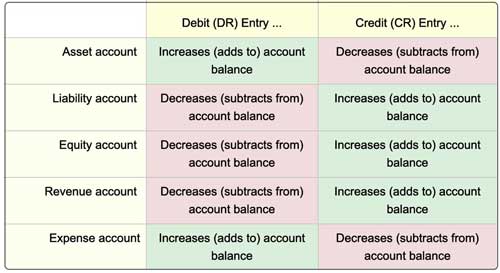

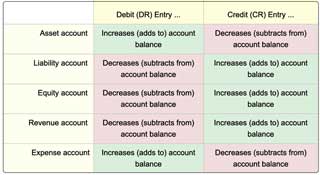

- Second, how different account categories use different rules for recording debit and credit transactions.

- Third, how contra-accounts work against other accounts in their own categories.

- Fourth, another business use for the term "Account," by which business firms and their customers refer to each other.

Contents

Accounting System Building Blocks

In business, each profit-making firm creates and uses an accounting system to manage and keep track of the company's:

- Incoming revenues and outgoing expenses.

- Assets, liabilities, and equities.

These five kinds of items, in fact, represent the five account categories in an accrual accounting system. As a result, the accrual accounting system also provides the basis for the financial reports the firm must file periodically.

The basic system building block is the account. An account is merely a recording place or holder for registering values and for one specific item or item class. Each account has the following properties:

- Account Category:

Revenue, Expense, Asset, Liability, or Equity.

All accounts must belong to one of these categories, although sub-categories also exist, as sections below explain, such as contra accounts or noncash accounts. - Unique Account Name and Number.

See Exhibit 5 Chart of Accounts below for examples. - A Balance.

- For Asset and Expense accounts, a positive balance is a Debit Balance.

- For Revenue, Liability, and Equity accounts, a positive balance is a Credit Balance.

The term account gives its name to the profession, Accounting or Accountancy. A practitioner with appropriate training and certification is an Accountant. The accountant's role is literally "keeper of the accounts."

Accounts in Five Basic Categories

Asset, Liability, Equity, Revenue, Expense

Each account serves to manage and track an item or item class. For accounting purposes, "items" appear in the above five above. And, for firms that use accrual accounting, these five are the only kinds of accounts possible in the accounting system.

Firstly, Accounting Systems Include

Three Kinds of Balance Sheet Accounts

- Asset accounts.

These represent items of value the firm owns or controls, and uses for earning revenues.

Example-1: Cash on Hand.

Example-2: Accounts Receivable.

Example-3: Property, Plant, & Equipment - Liability accounts.

Liabilities are debts the business owes to creditors. "Long-term liabilities" typically include obligations to lending firms and bondholders. Short-term liabilities, on the other hand, represent near-term debts incurred in operating the business.

Example-4: Accounts Payable.

Example-5: Salaries Payable.

Example-6: Bonds Payable. - Equity accounts.

Equities are items the firm owns outright. As such, "equities" represent owners claims to business assets.

Example-7: Owner Capital.

Example-8: Retained Earnings.

Double-entry accounting ensures that account balances, at all times maintain the "balance" in the so-called Balance Sheet Equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equities

Secondly, Accounting Systems

Include Two Kinds of Income Statement Accounts

- Revenue accounts.

In business, firms earn revenues from the sale of goods and services or investments.

Example-9: Product sales revenues

Example-10: Interest earned revenues - Expense accounts:

These accounts represent expenses incurred in the course of business.

Example-11: Direct labor costs

Example-12: Advertising expenses

At the end of the reporting period, firms report revenue and expense account balances in the structure of the Income statement equation:

Net Income = Revenues – Expenses

In reality, even a small business may identify a hundred or more such accounts for its accounting system, while a large firm may have many thousands. Nevertheless, for accounting purposes, all named accounts fall into one of the five categories above (see Chart of Accounts, below).

Debits and Credits for Different Account Categories

Transactions Change Account Balances

Every financial event for the company changes the balance of accounts. If the firm uses double-entry accounting (as nearly all companies do), every financial transaction causes two equal and offsetting changes to at least two different accounts. The impact in one is a "debit" (DR), and the change in another is a "credit" (CR).

Those unfamiliar with double-entry accounting sometimes assume that a "Credit" adds to the balance and that a "Debit" lowers the balance. This rule is sometimes true but not always. Many people are familiar with the terms debit and credit from managing their bank statements, on which banks "credit" (add to) and "debit (subtract from) their checking accounts.

In the double-entry system, however, whether a debit or a credit increases or decreases the account balance depends on the kind of account in view. The bank statement use is technically correct, but only because the checking account owner is—to the bank—a liability account. Liability category accounts increase with a credit and decrease with a debit.

Exhibit 1, below summarizes Debit and Credit impacts in the five account categories.

The Balance Sheet Always Balances

Debits and Credits Together Maintain the Balance

Suppose, for example, that a firm acquires assets valued at $100,000. As a result, the firm increases (debits) an asset account for $100,000. This impact could occur in "Account 163, Factory manufacturing equipment" from the Chart of Accounts below. Here, the increase is a debit because this is an asset account.

After just one debit transaction, however, the Balance sheet now needs an offsetting credit of $100,000 to another account to restore its balance. The offset could be either of the following:

- A credit of $100,000 to another asset account reduces that account value by $100,000. If the firm purchased with its cash, it could credit asset account "101, Cash on hand" to restore the Balance sheet balance.

- If instead, the firm finances the purchase with a bank loan, the offsetting transaction could be a credit to a liability account. Increasing (crediting) "Account 171, Bank loans payable" by $100,000 would restore the Balance sheet balance.

In this way, the basic accounting equation holds, and the Balance sheet always balances:

Assets = Liabilities + Equities

Also, for every pair of account entries that follow from a single transaction:

Debits = Credits

See the encyclopedia double-entry system for more on the accounting mathematics involved in double-entry accounting.

What is a Contra (Valuation Allowance) Account?

Contra Accounts Reverse the Rules

Not all accounts work additively with each other on the primary financial accounting reports. Sometimes one account works to offset the impact of another account of the same type. The so-called contra account work against other accounts in this way. And, in some situations, the contra accounts reverse the debit and credit rules from Exhibit 1 above.

Contra asset and contra liability accounts are also called valuation allowance accounts. They have this name because they work to adjust the book value, or carrying book value for assets or liabilities, as the examples below show.

Example: Balance Sheet Contra Accounts

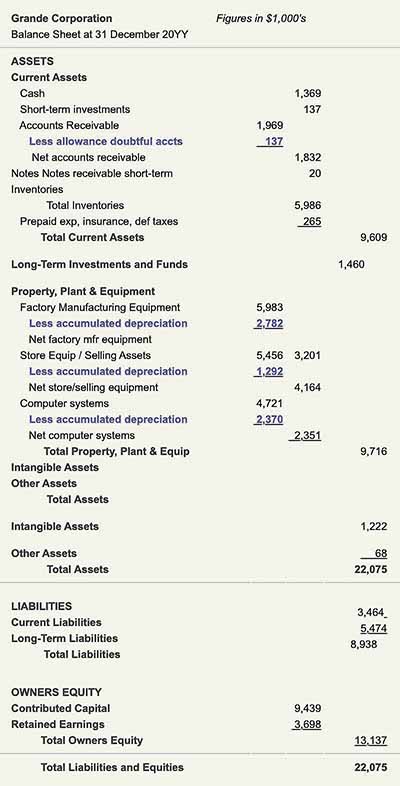

The Balance sheet example running throughout the Business Encyclopedia has several contra account examples. Under Balance sheet assets, for instance, these accounts include "Allowance for doubtful accounts" and "Accumulated depreciation. Exhibit 2, below, shows how the contra accounts work against other asset accounts, "Accounts receivable" and "Factory manufacturing equipment," "Store Equipment," and "Computer Systems." The contra account impacts are in blue.

You may notice from the Chart of Accounts in Exhibit 5 below, that "Accounts receivable" (Account 110) and "Allowance for doubtful accounts" (Account 120) are both asset accounts. "Allowance for doubtful accounts," however, is a contra asset account that reduces the impact (carrying value) contribution by Accounts receivable. The Balance sheet result is a "Net accounts receivable," somewhat less than the" Accounts receivable "value.

In the same way, Account 163, "Factory Manufacturing equipment" carries these asset values these assets at historical cost—the actual purchase price for these assets. This book value remains constant as long as the firm owns the assets. However, the asset's book value does reduce from year to year, as the Balance sheet shows. Contra Account 175, "Accumulated depreciation, factory manufacturing equipment," is subtracted from the Account 163 value, to produce the Balance sheet result "Net factory manufacturing equipment."

Depreciation Turns Asset Book Value Into Expense

Note, by the way, that depreciation expense works in this way to implement the accounting matching concept. This idea is the universal principle that firms report revenues when they earn them, matching them in the same period with the expenses that brought them.

The complication results from the accounting definition of expense: An expense is a decrease in owner's equity caused by the using up of assets. The funds for asset purchase are not an expense—at least not at the time of asset purchase. Accountants assume that assets use up their value over time, thereby incurring "expenses" over time. As a result, owners use depreciation methods o turn asset purchase price into depreciation expense, over time.

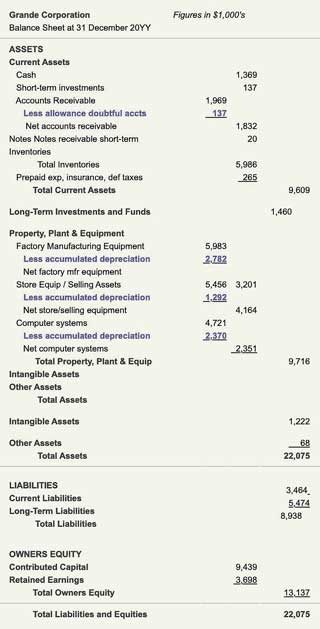

Two Journal Transactions for Writing Off Debt and Two for Charging Depreciation Expense

Each Balance sheet asset item in Exhibit 2, incidentally, also involves an Income statement Expense category account. These expense impacts appear on the Income statement, but not on the Balance sheet. In the first example, the expense account is "Bad debt expense," and in the second case, the expense account is "Depreciation expense, factory machinery." The offsetting debit and credit transactions might appear as follows in the bookkeeper's journal (the chronological record):

All four transactions add to the value of the accounts listed. Debiting each of the two expense accounts adds to account value, as you would expect from the table in Exhibit 1 above. However, notice here that crediting the two asset accounts adds to their value as well—just the opposite of what the same table prescribes for asset accounts. For contra accounts in this situation, the rules reverse, so that the basic equation, Debits = Credits, still holds for every pair of transactions. The examples also show why the balance in a contra asset account is a credit balance.

Contra Liability Accounts

The above examples show contra asset accounts, but there are also contra liability accounts that operate in the same way. For instance, under Balance sheet Liabilities, a long-term liability account "Bonds payable" may have with it a contra liability account such as "Discounts on bonds payable." The value in the contra account reduces the company's actual liability below the stated figure in the "Bonds payable" account.

Contra liability accounts—like their contra asset account counterparts—also reverse the debit-credit "rules" from the Exhibit 1 table above. An addition to a liability account is usually a credit, but a similar addition to a contra liability account is a debit. For this reason, a contra liability accounts balance is a debit balance, even though ordinary liability carry a credit balance.

Chart of Accounts and Accounting Cycle

Firms begin setting up a new accounting system by creating a Chart of Accounts. This chart is merely a list—the complete list—of named accounts the company expects to use for recording and reporting financial transactions. The Chart of Accounts thus defines the company's set of active accounts.

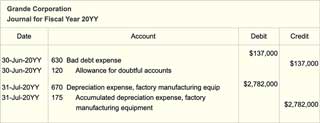

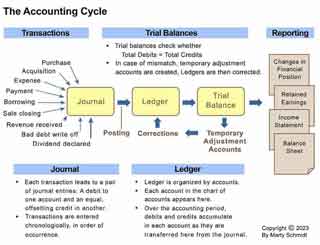

Accounts in the Accounting Cycle

The same list of accounts remains in view throughout the firm's entire accounting cycle. Business firms complete the full accounting cycle every reporting period. For public companies, this means ending a cycle every fiscal quarter as well fiscal year end. Exhibit 4 below, shows how account data move through the period.

Setting Up the Chart of Accounts

The first step in setting up an accounting system with a commercially-available accounting application, is creating the system's Chart of Accounts. The application will at the outset suggest account names and reference numbers for the Chart of Accounts. It will base suggestions on the size and complexity of the company and the nature of its business. Some small firms will merely use the program's default suggestions, but most will further tailor the list to fit their situations.

In any case, the accountant, consultant, or business owner setting up the Chart of Accounts should pursue several objectives for the chart:

- The chart must represent all five basic account categories (assets, liabilities, equities, revenues, and expenses).

- The chart should include enough accounts to provide the resolution the firm's accounting and finance specialists to control and manage operations effectively. They may need, therefore, to add quite a few additional accounts, especially where:

- The firm has a complex organizational structure.

- The firm has a complex cost structure.

- It produces and sells many different products or services.

- The firm has many customers, most of whom need their own "accounts."

- On the other hand, the accounting Materiality concept suggests that firms can disregard small, trivial, or items the firm rarely uses. When these transactions do occur, the accountant can enter them under the headings of a few more general and inclusive accounts—such as "Miscellaneous expense."

Reference Numbers Organize the Chart of Accounts.

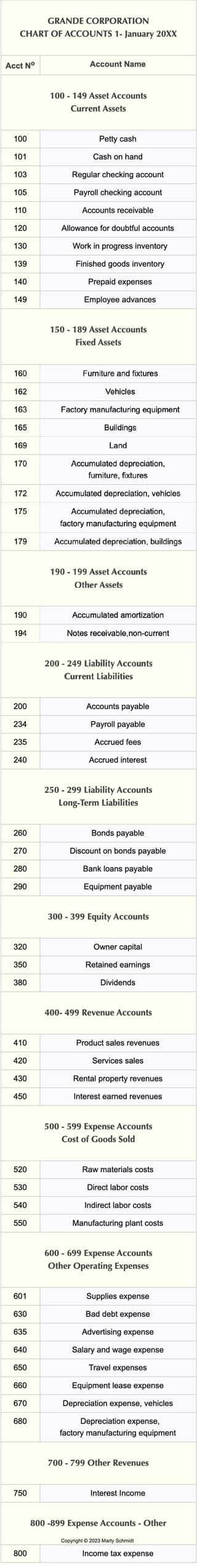

Notice that Exhibit 3 journal entries identify each account with both a number and name. And, the example Chart of Accounts in Exhibit 5, below, also shows account names with reference numbers (identifiers). In principle, these numbers can be anything. In practice, however, accountants use a numbering system that helps software and human accountants alike recognize immediately:

- The account category.

- The rank order of the account within its category.

Account numbering systems usually use 3 - 6 digits to identify each account. A typical 3-digit system might assign numbers as follows:

Three Digit Identifier System

100 - 199 Asset accounts

200 - 199 Liability accounts

300 - 399 Equity accounts

400 - 499 Revenue accounts primary business

500 - 599 Expense accounts - Cost of Goods Sold

600 - 699 Expense accounts - Other operating expenses

700 - 799 "Other revenue" (e.g., interest income)

800 - 899 "Other expenses" (e.g., income taxes)

The example Chart of Accounts in Exhibit 5, below, uses this 3-digit scheme. This approach allows for at most 100 individual accounts in each tier (e.g., Asset accounts). A 4-digit plan would, of course, designate asset accounts with the range 1000 - 1999, allowing for a possible 1,000 different accounts in that tier.

Regardless of how many digits the firm uses, numbering systems usually follow these principles:

- The first digit signals immediately the account category. Therefore, an account number beginning with 1, for instance, must be an asset account.

- The initial account number set should allow for later expansion. E.g., the chart might initially list Account 140, Prepaid Expenses, followed by Account 150, Employee Advances. If then, the firm needs to add accounts between these two, there are nine new account numbers available.

- Numbers after the first digit organize accounts roughly in order of currency.

- "Current asset" accounts have lower numbers than "Long-term asset" accounts for that reason.

- Current liabilities accounts have lower numbers than long-term liabilities accounts.

- Revenue and expense accounts carry numbers roughly in the order they appear on the Income statement.

Example Chart of Accounts

The Exhibit 5 Chart of Accounts, below, is just an extract from real a chart of accounts. The purpose of this version is to show the general approach to account numbering and naming. A complete example—even for a small company—would no doubt list many more accounts.

Accounts in Commerce and Financial Services

In many situations, customers enter a relationship with sellers by creating accounts with them. The relationship between seller and customer then differs from the customer-seller relationship involved in a one-time purchase transaction.

The account implies the relationship will continue for a time span, during which seller and customer have rights, privileges, and obligations towards each other. These are not available to those without the account relationship.

- Firms that sell to other businesses recognize repeat customers as accounts. The seller may designate one of its own sales staff as dedicated Account Manager for that customer. Account managers of this kind are responsible for account planning and building a continuing relationship with the customer. They are also responsible for sales performance with this customer.

- A bank customer with a bank account, for instance, has a right to deposit and withdraw funds, write checks against that account, and receive interest payments for funds on deposit. The bank (the seller) on the other hand, may use the depositor's funds for its investments and charge the account holder maintenance fees.

- Retail merchants sometimes recognize specific customers as accounts. Account holders may have the right to charge purchases with merchant-issued credit and make monthly payments on their account balance.

Sellers and service providers sometimes actually create for each customer an accounting system account. Banks, for instance, carry depositor customers as Liability accounts. And, the same banks recognize loan customers as Asset accounts.