What Is a Bookkeeping Journal?

Should anyone ask which transactions occurred on a given day, the journal provides the answer.

The vast majority of businesses, worldwide, rely on double-entry, accrual accounting to record, track, and report financial transactions. For these firms, every sale, purchase, payment, revenue receipt, disbursement, bank loan, bad debt, dividend, or expense calls for transactions that must enter the accounting system. This means that even very small organizations normally register quite a few transactions every business day. The normal point of entry for all such transactions is the bookkeeper's journal.

Define Journal

The Journal is a paper book or electronic record for capturing data about each financial transaction on the day it occurs or very shortly afterwards.

Journal entries accumulate in chronological order, showing readily the complete transaction history for any date.

For each transaction, the journal records at a minimum, (1) the account to impact (account name and number), (2) Date, (3) Amount or value, and (4) Credit or Debit nature of the transaction.

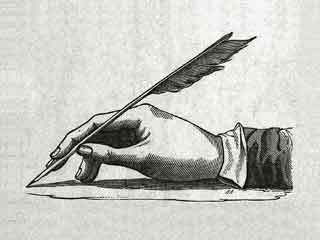

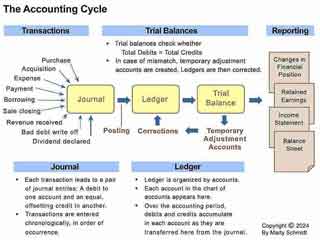

Transactions and their entry into an accounting journal are usually considered the first steps in the accounting cycle, as Exhibit 1 below shows. The exceptions are situations where entries are captured first in a daybook (or book of original entry) before they transfer to the journal.

The Journal

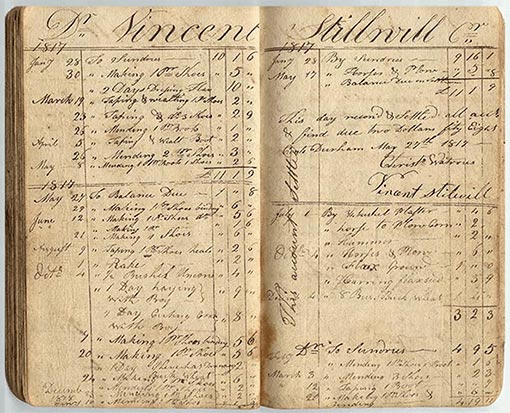

Historically, journals were always bound as sewn-page notebooks. Bookkeepers hand-wrote each entry in ink, shortly after the firm closed a sale, incurred an expense, earned revenues, or otherwise impacted the firm's accounts.

Today, of course, journals usually exist as part of an accounting system software application. Users, therefore, enter journal transactions either manually, through onscreen forms, or automatically, as with a point-of-sale system. Also, most accounting software systems provide user guidance and error-checking to help ensure that entries register correctly as debits or credits in the appropriate accounts. And, the software also automates the second stage of the accounting cycle, posting journal entries to a edger.

The name "journal," from Old French and Latin origins, suggests a daily activity (jour is French for "day"). Personal diaries and newspapers are sometimes called journals for the same reason. While other accounting records may update less frequently, journals update either continuously or at least daily. As a result, the journal builds a running list of account transactions as they occur. Consequently, should anyone ask which actions happened on a given day, the journal provides the answer.

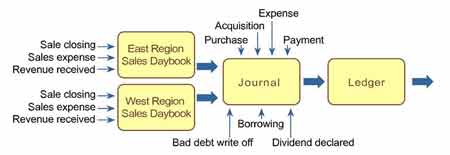

Daybooks

Some businesses use one or more daybooks (or books of original entry) instead of the journal as the first data entry point for transactions. Entries in daybooks build in chronological order, just as they do in journals. Entries in the firm's various daybooks are frequently transferred to the firm's journal, and then ultimately to the ledger. With daybooks, in other words, the journal becomes the second step in the accounting cycle, while the ledger becomes third.

Explaining Journal in Context

Sections below further define, explain and illustrate the term journal and example journal transactions, in context with related terms and concepts from the fields of accounting and bookkeepin, focusing on three themes:

- First, defining Journal, Daybook, and Book of Original Entry for bookkeeping and accounting purposes.

- Second, showing how different financial transactions impact accounts in five basic account categories..

- Third, contrasting Information the journal provides with information the ledger provides.

Contents

Journal Role in the Accounting Cycle

Exhibit 1. The accounting cycle. Transactions enter the journal as the first and second steps in the accounting cycle. The journal is a chronological record, where entries accumulate in the order they occur. Journal entries transfer (post) to a ledger, as the third step. Ledgers organize entries by account.

Most business firms record and report financial activity with a double-entry accounting system. Exhibit 1 above shows the significant steps in the accounting cycle for these firms. Note especially that the journal is the initial data entry point for transaction records. And, these records build ultimately into the firm's financial accounting reports at the end of the accounting cycle.

At various times, accountants copy (post) journal entries to a ledger—another record book. While the journal lists entries chronologically, the ledger organizes entries by account, as Exhibit 9, below, shows.

Near the end of each accounting period, accountants create a trial balance from the systems accounts, as part of an end-of-period check for accuracy. As a result, the trial balance should show that total debits equal total credits across all accounts. If the two totals do not agree, they make adjusting entries and corrections. Account names and balances then appear in the firm's financial accounting reports for the period.

The Daybook or Book of Original Entry

Why Use Daybooks?

Some firms add daybooks to the start of the accounting cycle, before the journal. Exhibit 2. above shows how the accounting cycle expands, slightly, when daybooks are present.

They add daybooks to the cycle when there is:

- A desire to put record-capturing into the hands of people directly engaging in transaction activity. These may include salespeople, warehouse receivers, maintenance personnel, or customer refund agents, for instance.

- A need to capture additional information beyond the essential transaction details for the journal. Daybook entries may also include useful data on customers, vendors, or the transaction event.

- A desire to keep together entries of one or another kind, for example:

- A sales daybook just for sales transactions. This is useful for keeping track of sales trends, or individual salesperson or sales team performance.

- A different sales daybook for each sales region. Using regional daybooks can be helpful when different regions need to be managed as different markets, with different market characteristics.

- A cash daybook for keeping cash transactions together. This is useful for keeping close watch on the companys working capital and cash flow.

Exhibit 2. above shows how the accounting cycle expands, slightly, when transactions enter the system through daybooks.

Daybooks Are to Journals As Sub-Ledgers Are to the General Ledger

Daybooks—when present—relate to the journal in the same way that sub-ledgers relate to the general ledger.

- First, the daybook (or sub-ledger) has the same structure as its parent, the journal (or general ledger).

- Second, transactions appear first in the daybook and then transfer, later, to the journal.

- Third, transactions post from the journal to sub-ledgers and then transfer, later, to the general ledger.

Initial transaction data move more or less continuously from daybooks to the journal. As a result, daybook transaction data such as account name and number, transaction amount, date, and type (debit or credit), move to the journal.

- Daybook entries may also include additional transaction data that do not transfer to the parent journal, such as customer details, salesperson, or sales location. Capturing and preserving such data is the daybook's reason for being.

In any case, daybook entries move to the journal in chronological order. And, in the journal, they appear as debits or credits to individual accounts from the firm's Chart of accounts.

Transactions For Different Accounts

Debit and Credit Impacts in 5 Account Types

The kind of impact that a debit or credit that a transaction makes on each ledger account depends on which of five Chart of Account categories the includes the account.

First, Three "Balance Sheet" Account Categories:

1. Asset accounts: Resources of value the business owns and uses.

Example: Cash on hand.

Example: Accounts Receivable.

2. Liability accounts: Debts the business owes.

Example: Accounts Payable.

Example: Salaries Payable.

3. Equity accounts: The owner's claim to business assets.

Example: Owner Capital.

Example: Retained Earnings.

Second, Two "Income Statement" Account Categories:

4. Revenue accounts: These can be, for example, earnings from selling goods and services, or investment income, or extraordinary income.

Example: Product Sales Revenues.

Example: Interest Earned Revenues.

5. Expense accounts: Expenses incurred in the course of business.

Example: Direct Labor Costs.

Example: Advertising Expenses.

In practice, even a small organization may list a hundred or more such accounts as the basis for its accounting system, and most organizations use many more. Nevertheless, for bookkeeping and accounting purposes, all named accounts fall into one of the five categories above.

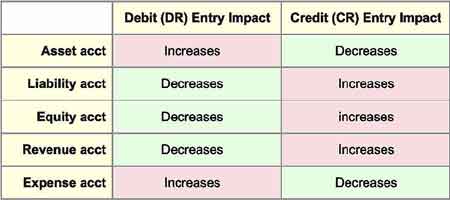

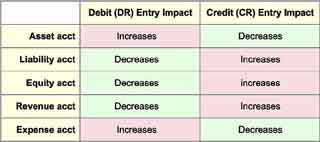

Adding and Subtracting With Debits and Credits

In double-entry accounting, every financial transaction brings at least two equal and offsetting account changes. The change in one account is called a debit (DR), and the impact in another is called a credit (CR). Whether a DR or a CR increases or decreases the account balance depends on the kind of account involved, as Exhibit 3 below shows.

Journal Account Entries

Suppose, for example, that a company acquires assets with $100,000. The journal entry for the acquisition will show that an asset account increases $100,000. This entry could be impact, for instance, an account "Factory manufacturing equipment." Because this is an asset account, its balance increase is a debit. However, the balance sheet is now temporarily out of balance until there is an offsetting credit of $100,000 to another account, somewhere in the system. The entry could be, for instance:

- A credit of $100,000 to another asset account, reducing that account value by $100,000. That account could be the asset account "Cash on Hand," representing cash for the asset purchase.

- If instead of using cash, the firm finances the purchase with a bank loan, the offsetting transaction in the journal entry would be a credit to a liability account. The result of that transaction could be a $100,000 increase to the liability account "Bank loans payable,"

The debit and the credit from the acquisition will appear together in the journal entry, but when they post to the ledger, each impact a different ledger account summary (see the journal and ledger entry examples below).

When the journal entry is complete, the fundamental accounting equation holds and the Balance sheet—as always—balances.

Assets = Liabilities + Equities

And, for the account journal entries that follow from a single transaction:

Debits = Credits

The Role of Contra Accounts

The bookkeeper or accountant dealing with journal and ledger entries faces one complication, however, in that not all accounts work additively with each other in financial accounting reports. In some cases, one account offsets the impact of another account in the same category. These are the contra accounts that "work against" other accounts in their categories.

Contra accounts work against others in the same category by reversing the debit and credit rules in Exhibit 3 above. For example, an "Accounts receivable" account and an "Allowance for doubtful accounts" account are both asset accounts. Note especially:

- "Accounts Receivable" carries a debit balance, meaning that a "debit" transaction to this account increases the account balance.

- "Allowance for Doubtful Accounts," however, is a "contra asset account ." The purpose of this account is ultimately to reduce the impact (balance) "Accounts receivable" contributes to the asset base.

- The contra asset account "Allowance for doubtful accounts" carries a credit balance, which means its value increases with a credit transaction.

When these journal entries make their way into financial reports, the Balance sheet result is a "Net Accounts Receivable" that is less than the Accounts receivable value.

In any case, the bookkeeper or accountant working with journal and ledger entries needs to have a solid command of double-entry bookkeeping rules. It also helps to have accounting software that provides clear guidance and careful error checking.

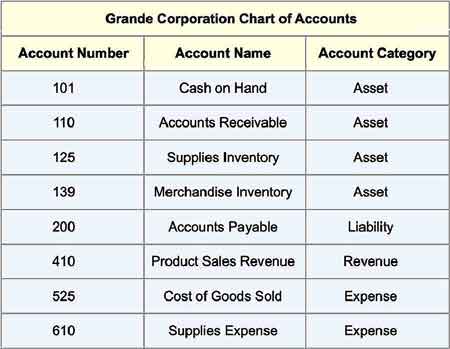

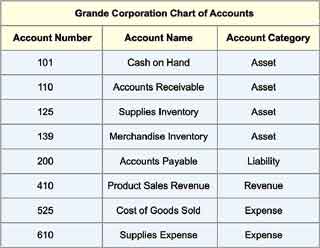

Entries for Accounts in the Chart of Accounts

This section illustrates journal entries and their contribution to ledger entries for a small subset of one company's chart of accounts. The examples involve only the very concise chart of accounts in Exhibit 4:

In reality, of course, the full chart of accounts, journal, and ledger will include many others not shown here. However, for one week's activity affecting these accounts, the journal and ledger entries might appear as the following section shows.

Define Your Terms!

Journal Entry, Debit, Credit, Chart of Accounts

Accounts are the basic building blocks of a a double-entry accounting system. Each account is a record of the value and changes in value for one specific purpose. When transactions enter the journal, those making entries are responsible for knowing which accounts to impact and whether the impacts should register as debits or credits.

Every organization that has its own accounting system maintains a fixed list of all the accounts that make up the accounting system. This list is the Chart of Accounts, and it is the authoritative last word on which accounts are active in the system and which are not. Every financial event impacts at least two or more of the specific accounts on the Chart.

The nature of the transaaction impact on an account depends on which of the five basic account categories has the account. The five account categories come in two groups.

Account Group 1:

Three "Balance Sheet" Account Categories:

- Asset Accounts.

Resources of value owned by the business and used for earning revenues. For example:

Cash on Hand

Accounts Receivable - Liability Accounts.

Debts and other financial obligations owed by the business. For instance:

Accounts Payable

Salaries Payable - Equity Accounts.

The owners claim to business assets. Equity is what owners own outright. For example:

Example: Owner capital

Example: Retained earnings

Acount Group 2:

Two "Income Statement" Account Categories:

- Revenue Accounts.

Money earned. For instance:

Product Sales Revenues

Interest Earned Revenues - Expense Accounts,

Expenses incurred in the course of business. For Example:

Direct labor costs

Advertising expenses

In practice, even a small firm may list a hundred or more such accounts as the basis for its accounting system, while larger and more complex organizations may use thousands. Nevertheless, for accounting purposes, all accounts fall into one of the five categories above.

Every Financial Event Brings At Least Two Journal Entries

Every financial event brings at least two equal and offsetting account changes. The change in one account is a debit (DR), and the impact to another is the opposite, a credit (CR). Whether a "debit" or a credit increases or decreases the account balance depends on the kind of account involved, as Exhibit 3 shows.

| Debit (DR) Entry | Credit (CR) Entry | |

|---|---|---|

| Asset acct | Increase account balance | Decrease account balance |

| Liability acct | Decrease account balance | Increase account balance |

| Equity acct | Decrease account balance | Increase account balance |

| Revenue acct | Decrease account balance | Increase account balance |

| Expense acct | Increase account balance | Decrease account balance |

| Exhibit 3. Debit and credit impacts on account balance depending on which category holds the account belongs. | ||

Suppose, for example, a firm purchases an asset for $100,000. Two journal entries must follow.

- Firstly, a journal entry for the acquisition shows an asset account increasing by $100,000. This account could be an asset account such as "Factory equipment." Because this is an asset account, the balance increase is a debit.

Secondly, however, the balance sheetis now temporarily out of balance until the firm makes an offsetting credit of $100,000 to another account somewhere in the system. This offsetting credit could be either of the following:

- A "credit" of $100,000 to another asset account, decreasing its balance by $100,000. This account could be the asset account "Cash on hand."

- If instead, the firm finances the asset purchase with a bank loan, the offsetting credit entry in the journal could be a credit to a liability account such as "Bank loans payable." As a result, the credit transaction increases the account balance by $100,000.

Double-Entry Rules Maintain Balance Sheet Balance.

Notice in the above example that the first transaction disturbs the Balance sheet balance, while the second transaction always restores the balance. Therefore, when both journal entries are complete, the basic accounting equation holds:

Assets = Liabilities + Equities

And, for the account journal entries that follow from a single transaction:

Debits = Credits

The Role of Contra Accounts

The bookkeeper or accountant dealing with journal entries faces one complication, however. Note that not all accounts work additively with each other on the financial accounting reports—especially on the Income statement and Balance sheet.

In some cases, one account offsets the impact of another of the same kind. These are the contra accounts that "work against" others in their categories. In some cases, the contra accounts reverse the debit and credit rules in Exhibit 3 above.

For example, "Allowance for doubtful accounts" and "Accounts receivable" are both asset accounts. Allowance for doubtful accounts, however, is also a contra asset account that ultimately reduces the impact (balance) of "Accounts receivable." When these journal entries make their way into the financial reports, the Balance sheet result is a "Net accounts receivable" that is less than the "Accounts receivable" value.

In any case, those working with journal entries must be familiar with the firm's chart of accounts and have a solid command of double-entry rules. And, they should be using accounting software that provides clear guidance and careful error checking.

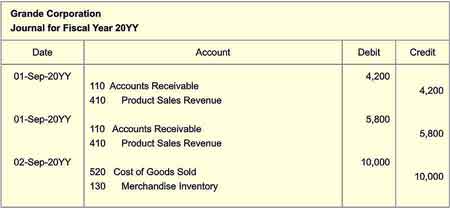

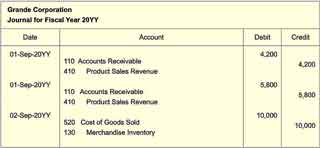

Example Journal Entries

On 1 September, two customers place product orders, on credit. Customer1 orders $4,200 in products, and Customer 2 orders $5,800 in products. The company ships the products the next day, 2 September.

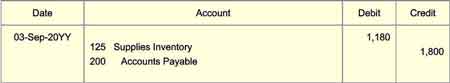

Journal Entry for 3 September

On 3 September, the company places a $1,180 order for office supplies:

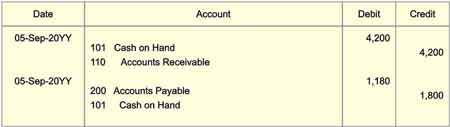

Journal Entries for 5 September

On 5 September, a written check from Customer 1 arrives ($4,200), and the company sends its bank check to the office supplies vendor ($1,180) for supplies ordered on 2 September:

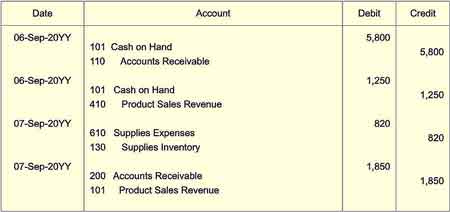

Journal Entries for 6 and 7 September

Four more events occur on 6 September:

- Customer 2 pays for goods in the 1 September order with a credit card ($5,800).

- Customer 3 uses cash to purchase products worth $1,250. The customer takes delivery immediately.

- Accountants find that supplies worth $820 have been used up since the last check of the supplies inventory.

- Customer 4 places a credit order for products ($1,850). This order did not ship by the day's end.

These transactions appear as follows;

A fast scan of the journal entries shows clearly that one part of the accounting equation holds, at least for these entries: Total debits = Total credits. The journal page shows clearly that every journal debit pairs with an equal, offsetting credit. The example also shows, that the journal, like the ledger, follows the practice of listing debit figures to the left of their companion credit figures.

The journal page does not show directly, however, whether or not the company is gaining or losing money. That picture is not entirely in view until the accounting period ends and ledger account balances come together on the income statement. That picture becomes more evident, however, when journal entries such as those above post to the ledger. The ledger summarizes transactions by account, showing each account's debits and credits. Ledger summaries usually show also how different account balances are running (e.g., balances for expense accounts and balances for sales revenue accounts).

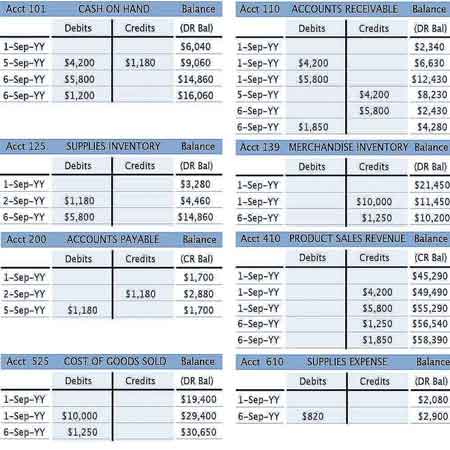

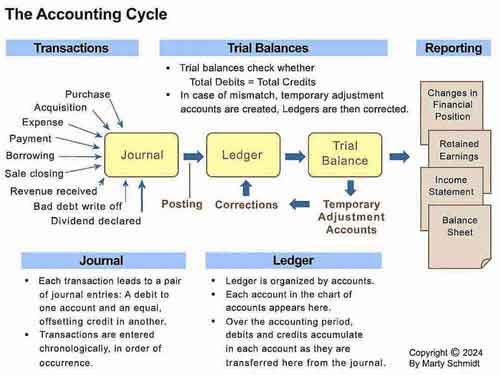

Example Ledger Entries

The second step in the accounting cycle is posting journal entries to the entity's general ledger. And, this step sometimes includes "posting" entries to various sub-ledgers as well.

Historically, when journals and ledgers were sewn-page notebooks, and bookkeepers and accountants made entries by hand, with pen and ink, accountants posted journal data into ledgers only periodically. That meant that they knew account balances only through the most recent posting. Software systems, however, usually update ledger accounts frequently or even continuously. Thus, running account balances in the ledger are always current, or nearly so, as Exhibit 4, below, suggests.

Account summaries in the ledger usually appear as T-accounts, as Exhibit 2 above shows. Exhibit 5 shows the T-account version for the eight accounts in Exhibit 3 and the journal entry examples above.