What Are Dividends?

Shareholder dividends are usually more reliable than other sources of investor returns, thereby increasing share prices.

Dividends are funds resulting from profitable operations that firms distribute directly to the firm's owners—the shareholders. Companies typically pay dividends to shareholders just after the end of a financial reporting period.

There are only two different ways that public companies can use earnings. After a successful period, a company can do either or both of the following:

- First pay some of the profits to shareholders as dividends.

- Second, keep the remainder as Retained Earnings.

Define Dividend

Dividends are funds resulting from profitable operations that firms distribute directly to the firm's owners—the shareholders.

Companies typically pay dividends to shareholders just after the end of a

financial reporting period.

Either action (paying dividends or retaining earnings) meets the textbook definition of a profit-making company's highest objective: increase owner value.

Dividends as Investment Income

"Since 1926 dividends have contributed to at least 45% of the total return of stocks in the S&P 500." — Michael Schmidt, Forbes, 20131

Those who buy shares of stock in public companies are rightfully called owners and investors at the same time, hoping for returns that exceed their costs. Owning shares in dividend-paying companies can provide a source of investor returns, in addition to potential gains from increasing share price. Dividend returns, moreover, tend to be be the more stable and predictable of these two kinds of returns, a consideration that share buyers and sellers take into account when setting share prices. For this reason, potential investors take a keen interest in studying company dividend histories, and pay close attention to analyst predictions on future dividend payments.

Omitting Dividends to Fund Rapid Growth

Many companies skip dividend payments entirely during rapid growth periods. All profits thus remain on the Balance Sheet as retained earnings, where they provide some of the capital the firm needs to fund growth. Skipping dividends reduces the company's need to raise capital by acquiring debt (as the company would by issuing bonds or taking bank loans). In such cases, shareholders do not receive dividends. Their compensation instead is an expectation: They expect share prices to keep growing, and they hope that company book value—Balance sheet equity—keeps growing.

It is also normal practice for these companies to initiate dividend payment when the rapid growth period ends. Some such companies find they must begin paying dividends to keep attracting investors and to hold share prices at acceptable levels.

Do Investments in Stock Shares Bring a Good Return on Investment?

Do investments in stock shares bring an attractive return on investment? Potential investors begin addressing such questions primarily by examining two sides of stock market investment analysis:

- Likely changes in share prices in the market.

- The likely timing and magnitudes of future dividend payments.

The two sides to the analysis are interrelated: whether or not a given dividend magnitude qualifies as a "good" return depends on share price, for instance. On the other hand, share price changes in the market depend on several factors, including likely dividend performance.

Explaining Dividends in Context

Sections below further define and explain dividends in context with other payment and investing terms, emphasizing four themes.

- First, explaining the nature and purpose of dividend payments to shareholder owners, including the role of firm's Board of Directors.

- Second, Explaining relevant date terms and their relationship to stock prices, including Ex-dividend date, Payment date, and Distribution date.

- Third, measuring and tracking company dividend performance with metrics such as Dividend Payout, Dividend Yield, and Dividend Growth.

- Fourth, explaining how firms report dividends declared and paid.

Contents

- What are Shareholder dividends?

- Must public companies declare and pay dividends?

- How often do firms declare and pay dividends?

- Define your terms! Essential date names for dividend payment.

- Do shareholders pay taxes on dividends they receive?

- How do investors and analysts measure dividend performance with Dividend Yield?

- Which metrics do investors use for comparing different dividend investments?

- How do firms report dividend payments? How do firms account for dividend actions?

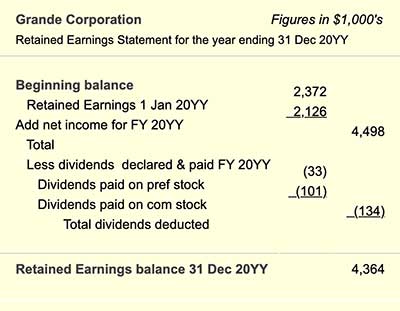

- Example Statement of Retained Earnings, with dividends.

Related Topics

- For a comprehensive introduction company reporting and Board actions, see Annual Report.

- The article Statement of Retained Earnings explains the role of dividend payments and retained earnings on the statement, in more depth.

Must Public Companies Declare and Pay Dividends?

When a reporting period ends with a profit, the company can choose to pay some of its income to shareholders, as dividends and keep the remaining earnings as "Retained earnings." Firms usually pay dividends as cash, although companies occasionally pay dividends as shares of stock or even other kinds of property sent to existing shareholders. The decision to pay or not pay dividends rests solely with the company's Boardof Directors.

Boards may choose to Omit Dividends

Public companies are free to determine the timing and magnitude of dividend payments. The decision to skip or pay dividends, and the size of the dividend payment, are always the responsibility of the Board of Directors. In some cases, however, boards may be merely endorsing the recommendations of corporate officers and other senior management.

Regulatory laws do not require companies to issue dividends—they may instead choose to channel all income from a reporting period to a "Retained Earnings" account (a Balance Sheet Equity account).

- Between 2005 and 2012, for instance, Apple, Inc. (based in the United States, stock symbol AAPL) paid no dividends on its common stock, despite record earnings growth during that period. For the fiscal year ended 24 September 2011, Apple reported a net income of about US$ 26 billion, of which the Apple Board declared $0 for dividends.

- For the period 2012 - 2017, however, Apple paid cash dividends to shareholders.

High Growth Firms Often Choose to Retain All Earnings

It is not unusual for technology and other high-grow companies to channel all earnings into Balance sheet equity by omitting dividends. Their Boards presume that the company's stock is still attractive absent dividend payment, and share prices will grow, due to increasing book value of the company and the promise of further earnings growth.

On the other hand, companies that prefer to attract shareholders who buy and hold their stock as a steady source of income pay dividends regularly.

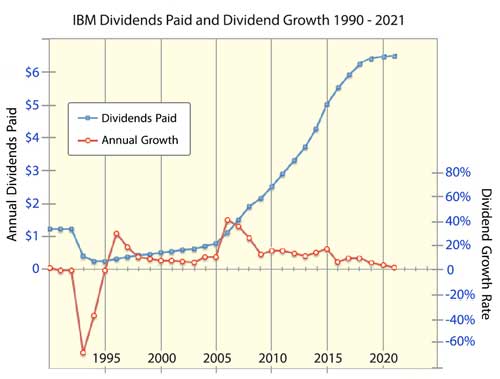

- IBM Corporation, (based in the United States, stock symbol IBM) has paid quarterly dividends regularly since1967. For the fiscal year ended 31 December 2016, IBM's reported net income after taxes was about US$ 11.82 billion. Of this, IBM's Board declared $5.3 billion as shareholder dividends.

How Often Do Companies Declare and Pay Dividends?

Public companies that pay dividends do so just after the end of a successful earnings period. Some firms choose to pay after every quarter, others pay every six months, and still, others pay only after the end of each fiscal year.

However, dividend declaration, payment amount, and payment timing are entirely at the discretion of the company's board of directors—except for one requirement that applies after a successful period:

If the Board is not willing or able to pay dividends on all shares, it must pay dividends on preferred shares before paying dividends on common stock shares.

Preferred share dividends, in other words, have preference over common share dividends.

Participating Preferred Shares: Additional Preferential Treatment.

Some companies issue a particular class of preferred shares called "Participating dividend shares." Whereas "ordinary" preferred shares may come with a regularly paid announced dividend, "participating dividend shares" come with a stipulation that shareholders receive additional dividend funds under certain conditions. That usually means the extra payment triggers when the common share dividend rises above the preferred share dividend.

In some companies, moreover, preferred shares carry cumulative dividend rights. These rights apply to situations where the Board declares dividends but does not pay them in the current reporting period or before the next dividend declaration date. Once the board declares preferred share dividends, the company is legally required to pay them before paying any "common share" dividends, even if payment has to wait until a future period. Dividends that have been declared but not yet paid are called dividends in arrears.

Firms Can Declare and Pay Dividends at Any Time

A company may declare and pay dividends at any time, with any frequency chosen by the company's directors. However, most dividend-paying public companies announce and regularly pay on a quarterly, semi-annual, or annual basis.

Through the end of 2021, for instance, for instance, IBM had declared and paid dividends consistently on a quarterly basis since 1967. Ericsson (based in Sweden, stock symbol ERIC) has paid dividends consistently on an annual basis since 2002.

Besides regular period dividend payments, companies may also declare and pay a special dividend at any time. The stock market may expect a 'special dividend' when a company has extraordinary gains (e.g., through a substantial sale of assets), or significant increases in operating profit. Such expectations can impact stock prices: For instance:

- Microsoft (MSFT) paid a special dividend in mid-2004, of $3.00 share. Then, In mid-2017, investment analysts and commentators (e.g., Forbes.com) were actively predicting that Microsoft (MSFT) would again issue a special dividend. The expert opinion thus expected a 2017 "special dividend" from Microsoft.

- At the end of 2011, Wynn Resorts Ltd. (WYNN) had declared and paid special dividends in each of the previous four years. Expectations of another special payment in 2011 were probably the main reason for a 25% increase in Wynn share price during 2011.

However, when Wynn announced financial results in October 2011 and made it clear that no special dividend would be forthcoming, the share price dropped immediately.

Essential Date Names in Dividend Payment

Note that firms always announce quarterly or annual corporate financial results publicly after a reporting period ends—usually several weeks afterward. Important dates regarding dividends follow:

Declaration Date

The Board of Directors may announce a decision on dividend payments when it announces financial results, or it may announce shortly afterwards. In any case, the day the firm announces is the declaration date. The Board's declaration on this date creates a legal obligation to pay dividends. The obligation shows up immediately in a "Dividends payable" account, a liability account.

Date of Record

On the declaration date, boards typically also announce a date of record, an ex-dividend date, and a pay date. Shareholders of record on the date of record will receive dividends. Those not on record on that date do not.

Ex-Dividend Date

Similar to the date of record, the dividend-paying firm declares the ex-dividend date. The ex-dividend date typically comes two or more business days before the date of record. Shares bought on or after the ex-dividend date do not come with the right to receive dividend payments even though they may be purchased slightly before the date of record. That is, those who buy shares on or after the ex-dividend date do not qualify with the company as dividend-receiving owners in time for the immediately forthcoming "date of record."

- The ex-dividend date is the critical dividend date for investors because share prices typically drop on ex-dividend date by an amount about equal to the per-share dividend.

- The trading day before the ex-dividend date is the in-dividend date. Shares trading on the in-dividend date are in-dividend shares or cum dividend shares, meaning they are "with the dividend."

- Shares trading on or after the ex-dividend date are ex-dividend shares. They typically sell at a lower price than they sold earlier as cum dividend shares.

Pay Date

On the declaration date, boards also announce a "pay date" for the dividend (or "payment date," or "distribution date"). On the "pay date," those who were registered owners on the "date of record" receive payment.

Example: IBM Dividend Dates for 2011

For example, for the fiscal quarter and year ended 31 December 2011, IBM announced financial results. The important dividend-related dates for IBM shareholders were:

Financial results announced: 21 January 2012

Declaration date: 31 January 2012

Ex-Dividend date: 8 February 2012

Date of record: 10 February 2012 ( 2 days after ex-dividend date)

Pay date: 10 March 2012

As expected, IBM's share price fell by the end of the ex-dividend date, but not by the full value of the declared dividend ($0.75/share). On 7 February (the "in-dividend date") IBM shares closed at $193.35. A day later (ex-dividend date) IBM shares closed $0.40 lower, at $192.95.

Dividend Yield Metric for Dividend Performance

The fundamental investment metric for evaluating and comparing dividend performances from stocks is the ratio dividend yield. The concept behind the metric is simple and easy to understand:

Dividend yield = The year's total dividends / share price.

This ratio compares investor's returns (dividends) directly to the cost of the investment (share price). Some analysts view the dividend yield metric as an instance of the cash flow financial metric "Return on investment" (simple ROI).

The dividend yield is easy to explain, but there is nevertheless room for confusion or misunderstanding with the concept. Consider a slightly more informative version of the above dividend yield formula:

Dividend yield = (Total annual dividends per share) / (Current share price)

The term current share price is interchangeable with prevailing share price. The formula has the same result using either share price term, "Current" or "Prevailing."

Expressing Dividend Yield as a Percentage

Analysts usually express dividend yield as a percentage. For IBM's fiscal year ending 31 December 2011, the company paid four quarterly dividends, totaling $3.00 per share for the year. When the IBM board declared final quarter dividends in February 2012, the IBM share price was about$188. At the time they declared IBM dividends, therefore:

Dividend Yield = $3 / $188

=1.60%

This example represents the most familiar form of dividend yield calculation. Notice that the dividend total in the formula refers to a complete year's dividend payments, whereas the share price refers to one point in time—the current value.

Of course, share prices can and usually do change every trading day, bringing a new dividend yield result with every change. It seems almost paradoxical that rising share prices—which increase the owner's potential value in the share investment—at the same time lower the measure of dividend performance. Because dividend yield can fluctuate from day to day and year to year, publishing analysts typically report a company's 5-year average dividend yield in addition to current dividend yield.

Trailing Annual Dividend Yield

When publishers make available dividend data, they may use the term trailing dividend yield (or trailing annual dividend yield), to signal that dividend yield derives from historical data (last year's dividend payments).

Analysts also publish estimates of forward dividend yield (or forward annual dividend yield), meaning the figure predicts next year's dividend yield based on the current share price and the analyst's predicted future dividend payments.

In brief, current dividend yield (or the equivalent trailing dividend yield) is history, while forward dividend yield is a forecast for the future that comes with some uncertainty.

Should investors compare dividend yield results directly to return on investment (ROI) estimates for other kinds of potential investments? Some business analysts challenge the notion that dividend yield is truly an ROI metric, saying that the metric does not compare directly to ROI figures from other kinds of investments for the following reasons:

- Simple return on investment, for business and investment analysis generally, assumes that both the "returns" and the "investment costs" in the ROI formula represent real cash flows.

- With dividend yield, however, "share price" in the formula is a hypothetical investor's opportunity cost for holding (for not selling) shares after collecting dividend payments.

Opportunity cost is an important and real consideration in investment analysis, but it is not cash flow. That reality may or may not disqualify dividend yield as a valid ROI metric, comparable to ROI results from other kinds of investments. Experts take different positions on that issue.

Other Metrics for Comparing Dividend Investments?

Potential investors seeking dividend income may choose from among many thousands of dividend-paying stocks. Naturally, they have a keen interest in financial metrics that help compare and evaluate potential stock investments. When professional analysts focus primarily on dividend performance, they rely on two versions of the dividend payout metric.

Dividend Payout

Dividend payout is a measure of the Board's propensity for paying dividends from income earnings. As such, the metric helps in estimating future dividend payments—if the company's overall financial performance and financial health remain strong (see the section below on Company Financial Metrics for Dividend Investors).

Dividend payout calculates from either of two formulas, both of which give the same result. The first and simpler approach requires (a) total dividends the Board declares for the period, and (b) net income for the same period.

[1] Dividend payout = Dividends declared / Net income

For example, for the fiscal year 2011, IBM's net income was about $15.86 billion. For the same fiscal year, IBM's Board declared about $3.47 billion in dividends. From these data:

Dividend payout = $3.47 billion / $15.86 billion

= 22%

The alternate formula for dividend payout uses the company's reported (a) dividends per share, and (b) earnings per share (EPS).

[2] Dividend payout = Dividends per share / Earnings per share

For the fiscal year 2011, IBM reported earnings per share (EPS) of about $13.08 and total dividends per share of $3.00. Using these figures in the second dividend payout formula brings the same result:

Dividend payout = $3.00 / $13.08

= 22%

Note that published EPS reports often use the label EPS(TTM), which indicates that the EPS figure is for the "Trailing twelve months" (preceding twelve months).

Some dividend investors consider a company's recent dividend payout history as an indicator of future dividend performance. Many prefer stocks with a consistent but relatively low dividend payout (less than 25%). A low payout, now, leaves room for dividend payout growth in the future.

Dividend Growth

For many dividend-paying companies, year-to-year dividend growth is regular and therefore somewhat easy to predict. Trends in Dividend growth—like the two dividend metrics above—are good indicators of a company's future dividend payments if the financial performance and financial health are stable (see Company Financial Metrics for Dividend Investors below).

Analysts typically measure dividend growth as an average rate at which dividend payments change, year to year.

One year's dividend growth calculates as:

1-Yr dividend growth = ( A - B) / B

Analysts normally write this ratio as a percentage, where

A = Most recent year's total over dividend per share

B = Previous year's total dividends paid per share

Exhibit 1, below, shows dividend growth information for IBM in graphical form.

Company Financial Metrics for Dividend Investors

Business firms declare and pay dividends from earnings—net income after taxes. The Boards of Directors who declare and pay dividends are concerned first with the company's long-term survival and growth.

- As long as the company's financial performance and financial health are robust, generous dividend payouts may support their objectives for the company's capital structure.

- On the other hand, boards may reduce or skip dividends when performance and health need improvement, as signaled by weak earnings growth, a debt/equity balance that needs adjustment, inadequate working capital, or other warning signs.

As a consequence, dividend investors will also pay close attention to traditional company financial metrics (or financial ratios) and their growth rates, such as

Reporting Dividend Actions

Example Retained Earnings Statement

For a profit-making public company, the Board of Directors designates how the firm will distribute income after each reporting period. They formally announce this distribution through the Statement of Retained Earnings. This statement shows how Income Statement profits from the period either transfer to the Balance sheet, as "Retained earnings," or to stockholders as "dividends."

In this way, the Statement of Retained Earnings serves as a bridge, or connecting link, between the Balance Sheet and Income Statement.

The Statement of Retained Earnings equation is as follows:

Net income = Preferred stock dividends paid

+ Common stock dividends paid

+ Retained earnings

and, equivalently

Retained earnings = Net income

– Preferred stock dividends paid

– Common stock dividends paid

Retained earnings, in other words, are the fuds that remain from net income after the firm pays dividends to shareholders.

Note that dividend payments are not considered expenses and do not appear on the Income Statement. Dividend payments are not expenses because they are taken from "net income" after subtracting all "expenses" from "revenues."

Each period's retained earnings add to the cumulative total from previous periods, to create the current retained earnings balance.

This example Statement of Retained Earnings in Exhibit 2 is from the same set of company reporting statements appearing throughout this encyclopedia. The statement set also includes an example Income Statement, Balance Sheet and Statement of Changes in Financial Position.